Designing Data Structures for Collaborative Apps

Introduction: Collaborative Apps via CRDTs

An extended version of this post appears on my personal site.

Suppose you’re building a collaborative app, along the lines of Google Docs/Sheets/Slides, Figma, Notion, etc., but without a central server. One challenge you’ll face is the actual collaboration: when one user changes the shared state, their changes need to show up for every other user. For example, if multiple users type at the same time in a text field, the result should reflect all of their changes and be consistent (identical for all users).

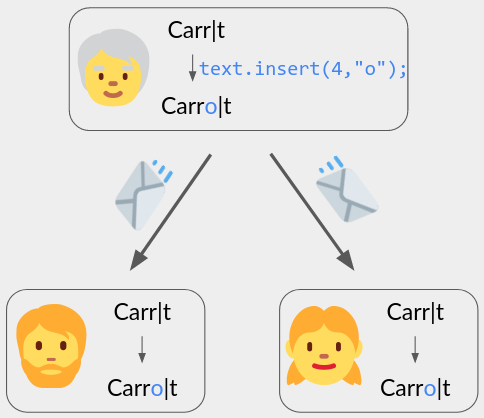

Conflict-free Replicated Data Types (CRDTs) provide a solution to this challenge. They are data structures that look like ordinary data structures (maps, sets, text strings, etc.), except that they are collaborative: when one user updates their copy of a CRDT, their changes automatically show up for everyone else. Each user sees their own changes immediately, while under the hood, the CRDT broadcasts a message describing the change to everyone else. Other users see the change once they receive this message.

Note that multiple users might make changes at the same time, e.g., both typing at once. Since each user sees their own changes immediately, their views of the document will temporarily diverge. However, CRDTs guarantee that once the users receive each others’ messages, they’ll see identical document states again: this is the definition of CRDT correctness. Ideally, this state will also be “reasonable”, i.e., it will incorporate both of their edits in the way that the users expect.

In distributed systems terms, CRDTs are Available, Partition tolerant, and have Strong Eventual Consistency.

CRDTs work even if messages might be arbitrarily delayed, or delivered to different users in different orders. This lets you make collaborative experiences that don’t need a central server, work offline, and/or are end-to-end encrypted (local-first software).

CRDTs allow offline editing, unlike Google Docs.

I’m particularly excited by the potential for open-source collaborative apps that anyone can distribute or modify, without requiring app-specific hosting.

The Challenge: Designing CRDTs

Having read all that, let’s say you choose to use a CRDT for your collaborative app. All you need is a CRDT representing your app’s state, a frontend UI, and a network of your choice (or a way for users to pick the network themselves). But where do you get a CRDT for your specific app?

If you’re lucky, it’s described in a paper, or even better, implemented in a library. But those tend to have simple or one-size-fits-all data structures: maps, text strings, unstructured JSON, etc. You can usually rearrange your app’s state to make it fit in these CRDTs; and if users make changes at the same time, CRDT correctness guarantees that you’ll get some consistent result. However, it might not be what you or your users expect. Worse, you have little leeway to customize this behavior.

In a published JSON CRDT, when representing a todo-list using items with "title" and "done" fields, you can end up with an item {"done": true} having no "title" field. Image credit: Figure 6 from the paper.

This blog post will instead teach you how to design CRDTs from the ground up. I’ll present a few simple CRDTs that are obviously correct, plus ways to compose them together into complicated whole-app CRDTs that are still obviously correct. I’ll also present principles of CRDT design to help guide you through the process. To cap it off, we’ll design a CRDT for a collaborative spreadsheet.

Ultimately, I hope that you will gain not just an understanding of some existing CRDT designs, but also the confidence to tweak them and create your own!

Related Work

The CRDTs I describe are based on Shapiro et al. 2011 unless noted otherwise. However, the way I describe them, and the design principles and composition techniques, are my own way of thinking about CRDT design. It’s inspired by the way Figma and Hex describe their collaboration platforms; they likewise support complex apps by composing simple, easy-to-reason-about pieces. Relative to those platforms, I incorporate more academic CRDT designs, enabling more flexible behavior and server-free operation.

Basic Designs

I’ll start by going over some basic CRDT designs.

Unique Set

Our foundational CRDT is the Unique Set. It is a set in which each added element is considered unique.

Formally, the user-facing operations on the set, and their collaborative implementations, are as follows:

add(x): Adds an elemente = (t, x)to the set, wheretis a unique new tag, used to ensure that(t, x)is unique. To implement this, the adding user generatest, e.g., as a pair (device id, device-specific counter), then serializes(t, x)and broadcasts it to the other users. The receivers deserialize(t, x)and add it to their local copy of the set.delete(e): Deletes the elemente = (t, x)from the set. To implement this, the deleting user serializestand broadcasts it to the other users. The receivers deserializetand remove the element with tagtfrom their local copy, if it has not been deleted already.

The lifecycle of an add or delete operation.

When displaying the set to the user, you ignore the tags and just list out the data values x, keeping in mind that (1) they are not ordered (at least not consistently across different users), and (2) there may be duplicates.

Example: In a collaborative flash card app, you could represent the deck of cards as a Unique Set, using x to hold the flash card’s value (e.g., its front and back strings). Users can edit the deck by adding a new card or deleting an existing one, and duplicate cards are allowed.

When broadcasting messages, we require that they are delivered reliably and in causal order, but it’s okay if they are arbitarily delayed. (These rules apply to all CRDTs, not just the Unique Set.) Delivery in causal order means that if a user sends a message \(m\) after receiving or sending a message \(m^\prime\), then all users delay receiving \(m\) until after receiving \(m^\prime\). This is the strictest ordering we can implement without a central server and without extra round-trips between users, e.g., by using vector clocks.

Messages that aren’t ordered by the causal order are concurrent, and different users might receive them in different orders. But for CRDT correctness, we must ensure that all users end up in the same state regardless, once they have received the same messages.

For the Unique Set, it is obvious that the state of the set, as seen by a specific user, is always the set of elements for which they have received an add message but no delete messages. This holds regardless of the order in which they received concurrent messages. Thus the Unique Set is correct.

Note that delivery in causal order is important—a

deleteoperation only works if it is received after its correspondingaddoperation.

We now have our first principle of CRDT design:

Principle 1. Use the Unique Set CRDT for operations that “add” or “create” a unique new thing.

Although it is simple, the Unique Set forms the basis for the rest of our CRDTs.

Lists

Our next CRDT is a list CRDT. It represents a list of elements, with insert and delete operations. For example, you can use a list CRDT of characters to store the text in a collaborative text editor, using insert to type a new character and delete for backspace.

Formally, the operations on a list CRDT are:

insert(i, x): Inserts a new element with valuexat indexi, between the existing elements at indicesiandi+1. All later elements (index>= i+1) are shifted one to the right.delete(i): Deletes the element at indexi. All later elements (index>= i+1) are shifted one to the left.

We now need to decide on the semantics, i.e., what is the result of various insert and delete operations, possibly concurrent. The fact that insertions are unique suggests using a Unique Set (Principle 1). However, we also have to account for indices and the list order.

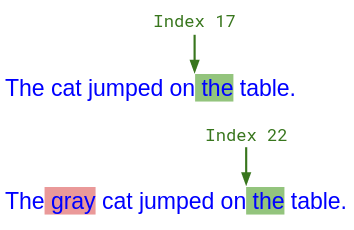

One approach would use indices directly: when a user calls insert(i, x), they send (i, x) to the other users, who use i to insert x at the appropriate location. The challenge is that your intended insertion index might move around as a result of users’ inserting/deleting in front of i.

Alice typed " the" at index 17, but concurrently, Bob typed " gray" in front of her. From Bob's perspective, Alice's insert should happen at index 22.

It’s possible to work around this by “transforming” i to account for concurrent edits. That idea leads to Operational Transformation (OT), the earliest-invented approach to collaborative text editing, and the one used in Google Docs and most existing apps. Unfortunately, OT algorithms are quite complicated, leading to numerous flawed algorithms. You can reduce complexity by using a central server to manage the document, like Google Docs does, but that precludes decentralized networks, end-to-end encryption, and server-free open-source apps.

List CRDTs use a different perspective from OT. When you type a character in a text document, you probably don’t think of its position as “index 17” or whatever; instead, its position is at a certain place within the existing text.

“A certain place within the existing text” is vague, but at a minimum, it should be between the characters left and right of your insertion point (“on” and “ table“ in the example above) Also, unlike an index, this intuitive position is immutable.

This leads to the following implementation. The list’s state is a Unique Set whose values are pairs (p, x), where x is the actual value (e.g., a character), and p is a unique immutable position drawn from some abstract total order. The user-visible state of the list is the list of values x ordered by their positions p. Operations are implemented as:

insert(i, x): The inserting user looks up the positionspL,pRof the values to the left and right (indicesiandi+1), generates a unique new positionpsuch thatpL < p < pR, and callsadd((p, x))on the Unique Set.delete(i): The deleting user finds the elementeof the Unique Set at indexi, then callsdelete(e)on the Unique Set.

Of course, we need a way to create the positions p. That’s the hard part—in fact, the hardest part of any CRDT—and I don’t have space to go into it here; you should use an existing algorithm (e.g., RGA) or implementation (e.g., Yjs’s Y.Array).

The important lesson here is that we had to translate indices (the language of normal, non-CRDT lists) into unique immutable positions (what the user intuitively means when they say “insert here”). That leads to our second principle of CRDT design:

Principle 2. Express operations in terms of user intention—what the operation means to the user, intuitively. This might differ from the closest ordinary data type operation.

Registers

Our last basic CRDT is the register. This is a variable that holds an arbitrary value that can be set and get. If multiple users set the value at the same time, you pick one of them arbitrarily, or perhaps average them together.

Example uses for registers:

- The font size of a character in a collaborative rich-text editor.

- The name of a document.

- The color of a specific pixel in a collaborative whiteboard.

- Basically, anything where you’re fine with users overwriting each others’ concurrent changes and you don’t want to use a more complicated CRDT.

Registers are very useful and suffice for many tasks (e.g., Figma and Hex use them almost exclusively).

The only operation on a register is set(x), which sets the value to x (in the absence of concurrent operations). We can’t perform these operations literally, since if two users receive concurrent set operations in different orders, they’ll end up with different values.

However, we can add the value x to a Unique Set, following Principle 1. The state is now a set of values instead of a single value, but we’ll address that soon. We can also delete old values each time set(x) is called, overwriting them.

Thus the implementation of set(x) becomes:

- For each element

ein the Unique Set, calldelete(e)on the Unique Set; then calladd(x).

The result is that at any time, the register’s state is the set of all the most recent concurrently-set values.

Loops of the form “for each element of a collection, do something” are common in programming. We just saw a way to extend them to CRDTs: “for each element of a Unique Set, do some CRDT operation”. I call this a causal for-each operation because it only affects elements that are prior to the for-each operation in the causal order. It’s useful enough that we make it our next principle of CRDT design:

Principle 3a. For operations that do something “for each” element of a collection, one option is to use a causal for-each operation on a Unique Set (or list CRDT).

(Later we will expand on this with Principle 3b, which also concerns for-each operations.)

Returning to registers, we still need to handle the fact that our state is a set of values, instead of a specific value.

One option is to accept this as the state, and present all conflicting values to the user. That gives the Multi-Value Register (MVR).

Another option is to pick a value arbitrarily but deterministically. E.g., the Last-Writer Wins (LWW) Register tags each value with the wall-clock time when it is set, then picks the value with the latest timestamp.

![]()

In Pixelpusher, a collaborative pixel art editor, each pixel shows one color by default (LWW Register), but you can click to pop out all conflicting colors (MVR). Image credit: Peter van Hardenberg (original).

In general, you can define the value getter to be an arbitrary deterministic function of the set of values.

Examples:

- If the values are colors, you can average their RGB coordinates.

- If the values are booleans, you can choose to prefer

truevalues, i.e., the register’s value istrueif its set contains anytruevalues. That gives the Enable-Wins Flag.

Composing CRDTs

We now have enough basic CRDTs to start making more complicated data structures through composition. I’ll describe three techniques: CRDT objects, CRDT-valued maps, and collections of CRDTs.

CRDT Objects

The simplest composition technique is to use multiple CRDTs side-by-side. By making them instance fields in a class, you obtain a CRDT Object, which is itself a CRDT (trivially correct). The power of CRDT objects comes from using standard OOP techniques, e.g., implementation hiding.

Examples:

- In a collaborative flash card app, to make individual cards editable, you could represent each card as a CRDT object with two text CRDT (list CRDT of characters) instance fields, one for the front and one for the back.

- You can represent the position and size of an image in a collaborative slide editor by using separate registers for the left, top, width, and height.

To implement a CRDT object, each time an instance field requests to broadcast a message, the CRDT object broadcasts that message tagged with the field’s name. Receivers then deliver the message to their own instance field with the same name.

CRDT-Valued Map

A CRDT-valued map is like a CRDT object but with potentially infinite instance fields, one for each allowed map key. Every key/value pair is implicitly always present in the map, but values are only explicitly constructed in memory as needed, using a predefined factory method (like Apache Commons’ LazyMap).

Examples:

- Consider a shared notes app in which users can archive notes, then restore them later. To indicate which notes are normal (not archived), we want to store them in a set. A Unique Set won’t work, since the same note can be added (restored) multiple times. Instead, you can use a CRDT-valued map whose keys are the documents and whose values are enable-wins flags; the value of the flag for key

docindicates whetherdocis in the set. This gives the Add-Wins Set. - Quill lets you easily display and edit rich text in a browser app. In a Quill document, each character has an

attributesmap, which contains arbitrary key-value pairs describing formatting (e.g.,"bold": true). You can model this using a CRDT-valued map with arbitrary keys and LWW register values; the value of the register for keyattrindicates the current value forattr.

A CRDT-valued map is implemented like a CRDT object: each message broadcast by a value CRDT is tagged with its serialized key. Internally, the map stores only the explicitly-constructed key-value pairs; each value is constructed using the factory method the first time it is accessed by the local user or receives a message. However, this is not visible externally—from the outside, the other values still appear present, just in their initial states. (If you want an explicit set of “present” keys, you can track them using an Add-Wins Set.)

CRDT-valued maps are based on the Riak map.

Collections of CRDTs

Our above definition of a Unique Set implicitly assumed that the data values x were immutable and serializable (capable of being sent over the network). However, we can also make a Unique Set of CRDTs, whose values are dynamically-created CRDTs.

To add a new value CRDT, a user sends a unique new tag and any arguments needed to construct the value. Each recipient passes those arguments to a predefined factory method, then stores the returned CRDT in their copy of the set. When a value CRDT is deleted, it is forgotten and can no longer be used.

Note that unlike in a CRDT-valued map, values are explicitly created (with dynamic constructor arguments) and deleted—the set effectively provides collaborative new and free operations.

We can likewise make a list of CRDTs.

Examples:

- In a shared folder containing multiple collaborative documents, you can define your document CRDT, then use a Unique Set of document CRDTs to model the whole folder. (You can also use a CRDT-valued map from names to documents, but then documents can’t be renamed, and documents “created” concurrently with the same name will end up merged.)

- Continuing the Quill rich-text example from the previous section, you can model a rich-text document as a list of “rich character CRDTs”, where each “rich character CRDT” consists of an immutable (non-CRDT) character plus the

attributesmap CRDT. This is sufficient to build a simple Google Docs-style app with CRDTs (source).

Using Composition

You can use the above composition techniques and basic CRDTs to design CRDTs for many collaborative apps. Choosing the exact structure, and how operations and user-visible state map onto that structure, is the main challenge.

A good starting point is to design an ordinary (non-CRDT) data model, using ordinary objects, collections, etc., then convert it to a CRDT version. So variables become registers, sets become Unique Sets or Add-Wins Sets, etc. You can then tweak the design as needed to accommodate extra operations or fix weird concurrent behaviors.

To accommodate as many operations as possible while preserving user intention, I recommend:

Principle 4. Independent operations (in the user’s mind) should act on independent state.

Examples:

- As mentioned earlier, you can represent the position and size of an image in a collaborative slide editor by using separate registers for the left, top, width, and height. If you wanted, you could instead use a single register whose value is a tuple (left, top, width, height), but this would violate Principle 4. Indeed, then if one user moved the image while another resized it, one of their changes would overwrite the other, instead of both moving and resizing.

- Again in a collaborative slide editor, you might initially model the slide list as a list of slide CRDTs. However, this provides no way for users to move slides around in the list, e.g., swap the order of two slides. You could implement a move operation using cut-and-paste, but then slide edits concurrent to a move will be lost, even though they are intuitively independent operations.

Following Principle 4, you should instead implement move operations by modifying some state independent of the slide itself. You can do this by replacing the list of slides with a Unique Set of objects{ slide, positionReg }, wherepositionRegis an LWW register indicating the position. To move a slide, you create a unique new position like in a list CRDT, then set the value ofpositionRegequal to that position. This construction gives the list-with-move CRDT.

New: Concurrent+Causal For-Each Operations

There’s one more trick I want to show you. Sometimes, when performing a for-each operation on a Unique Set or list CRDT (Principle 3a), you don’t just want to affect existing (causally prior) elements. You also want to affect elements that are added/inserted concurrently.

For example:

- In a rich text editor, if one user bolds a range of text, while concurrently, another user types in the middle of the range, the latter text should also be bolded.

In other words, the first user’s intended operation is “for each character in the range including ones inserted concurrently, bold it”. - In a collaborative recipe editor, if one user clicks a “double the recipe” button, while concurrently, another user edits an amount, then their edit should also be doubled. Otherwise, the recipe will be out of proportion, and the meal will be ruined!

I call such an operation a concurrent+causal for-each operation. To accomodate the above examples, I propose the following addendum to Principle 3a:

Principle 3b. For operations that do something “for each” element of a collection, another option is to use a concurrent+causal for-each operation on a Unique Set (or list CRDT).

To implement this, the initiating user first does a causal for-each operation. They then send a message describing how to perform the operation on concurrently added elements. The receivers apply the operation to any concurrently added elements they’ve received already (and haven’t yet deleted), then store the message in a log. Later, each time they receive a new element, they check if it’s concurrent to the stored message; if so, they apply the operation.

Concurrent+causal for-each operations are novel as far as I’m aware. They are based on a paper I, Heather Miller, and Christopher Meiklejohn wrote last year, about a composition technique we call the semidirect product, which can implement them (albeit in a confusing way).

[an error occurred while processing this directive]Finished Design

In summary, the state of our spreadsheet is as follows.

// ---- CRDT Objects ----

class Row {

height: LWWRegister<number>;

isVisible: EnableWinsFlag;

// ...

}

class Column {

width: LWWRegister<number>;

isVisible: EnableWinsFlag;

// ...

}

class Cell {

content: LWWRegister<string>;

fontSize: LWWRegister<number>;

wordWrap: EnableWinsFlag;

// ...

}

class ListWithMove<C> {

state: UniqueSet<{value: C, positionReg: LWWRegister<ListCRDTPosition>}>;

}

// ---- App state ----

rows: ListWithMove<Row>;

columns: ListWithMove<Column>;

cells: CRDTValuedMap<[row: Row, column: Column], Cell>;

Note that I never explicitly mentioned CRDT correctness—the claim that all users see the same document state after receiving the same messages. Because we assembled the design from existing CRDTs using composition techniques that preserve CRDT correctness, it is trivially correct. Plus, it should be straightforward to reason out what would happen in various concurrency scenarios.

As exercises, here are some further tweaks you can make to this design, phrased as user requests:

- “I’d like to have multiple sheets in the same document, accessible by tabs at the bottom of the screen, like in Excel.” Hint (highlight to reveal): Use a list of CRDTs.

- “I’ve noticed that if I change the font size of a cell, while at the same time someone else changes the font size for the whole row, sometimes their change overwrites mine. I’d rather keep my change, since it’s more specific.” Hint: Use a register with a custom getter.

- “I want to reference other cells in formulas, e.g.,

= A2 + B3. Later, ifB3moves toC3, its references should update too.” Hint: Store the reference as something immutable.

Conclusion

I hope you’ve gained an understanding of how CRDTs work, plus perhaps a desire to apply them in your own apps. We covered a lot:

- Traditional CRDTs: Unique Set, List/Text, LWW Register, Enable-Wins Flag, Add-Wins Set, CRDT-Valued Map, and List-with-Move.

- Novel Operations: Concurrent+causal for-each operations on a Unique Set or list.

- Whole Apps: Spreadsheet, rich text, and pieces of various other apps.

For more info, crdt.tech collects most CRDT resources in one place.

I’ve also started putting these ideas into practice in a library, Collabs. You can learn more about Collabs, and see how open-source collaborative apps might work in practice, in my Strange Loop talk.

Acknowledgments

I thank Justine Sherry, Jonathan Aldrich, and Pratik Fegade for reviewing this post and giving helpful feedback. I also thank Heather Miller, Ria Pradeep, and Benito Geordie for numerous CRDT design discussions that led to these ideas.