Grounding Neural Inference with Satisfiability Modulo Theories: Leveraging Theory Solvers for Machine Learning

Introduction: The Dual Challenge of Perception and Reasoning

Modern AI excels at pattern recognition but suffers when faced with logical reasoning tasks. What happens when we ask a neural network to solve a Sudoku puzzle from an image, verify a mathematical proof, or diagnose a medical condition based on a set of symptoms and rules? These tasks highlight a fundamental gap in current AI capabilities.

Tasks that require both perception and deductive reasoning present a significant challenge for traditional neural architectures. Despite advances in large language models, even models like GPT-4 still struggle with tasks that require precise logical reasoning. For instance, in 2023 there was a prediction market questioning GPT-4’s ability to solve even easy Sudoku puzzles correctly, despite its impressive capabilities in other domains.

Many problems naturally decompose into two parts:

- Perception : Taking unstructured data and giving it meaning

- Deduction : Taking semantically structured inputs and producing results according to well-defined rules

This research explores integrating neural networks with Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT) solvers to enhance reasoning capabilities while maintaining perceptual strengths of neural networks.

The Challenge of Neural Reasoning

Despite impressive pattern recognition capabilities, neural networks struggle with logical reasoning tasks. This gap becomes evident in problems that humans solve through a combination of perception and deduction.

The process in traditional neural networks is entirely data-driven . Large language models arrive at correct results based on patterns learned from training data but without explicit reasoning or understanding of numerical logic . When faced with examples that deviate from common patterns seen during training, these models often fail, suggesting their lack of true logical reasoning capabilities.

Neural networks have demonstrated impressive capabilities in pattern recognition tasks across various domains, including vision, language, and audio processing. However, when faced with tasks that require logical reasoning, these models often struggle to maintain consistency and reliability. This gap becomes particularly evident in problems that humans solve through a combination of perception and deductive reasoning:

- Visual Algebra : Recognizing an equation like “y - 2 = 10” from an image and solving for the variable

- Visual Sudoku : Identifying digits in a Sudoku grid and finding a valid solution

- Code Synthesis : Generating correct code from a docstring that performs the specified function

Other potential use-cases could be medical diagnoses – interpreting patient symptoms through medical imaging and then applying diagnostic rules; legal uses – interpreting the raw text of a legal statement and applying laws to them, and semantic parsing – converting natural language to logical form for database queries.

Why do neural networks struggle with these seemingly straightforward tasks? Previous studies on visual Sudoku suggested that learning the rules is challenging without tailored priors. Even in scenarios where rules are learnable, using neural inference to apply them consistently poses challenges. Despite efforts to tune LLMs like GPT to solve such problems, they can’t do so reliably.

Solver Layers Bridge Neural Networks and Logical Reasoning

To address these limitations, “solver layers” can be integrated into neural network architectures. A solver layer is a module whose functionality is primarily driven by a symbolic tool. These layers act as an interface between neural networks and logical or combinatorial optimization systems. Previous work includes integrating boolean satisfiability (SAT) solvers with neural networks, treating combinatorial algorithms as black-box layers, and developing systems for differentiable logic programming. We describe them in more detail below.

The solver layer approach offers several advantages:

-

Incorporation of Domain Knowledge : Instead of requiring the model to learn complex logical rules from data, solver layers allow direct encoding of known constraints and relationships. This is particularly valuable in domains with well-established rules, like mathematics, programming, or games.

-

Consistency Guarantees : By enforcing logical constraints through solvers, the system can guarantee that outputs will satisfy certain properties, leading to more reliable and predictable behavior.

-

Improved Sample Efficiency : Since the model doesn’t need to learn logical rules from data, it can focus learning on the perception task, potentially requiring less training data overall.

-

Enhanced Generalization : Models with solver layers can often generalize better to new examples that follow the same logical rules but differ in surface features, as the rules are explicitly encoded rather than implicitly learned.

But how do these advantages translate to practical applications? Consider a real-world example:

In a Sudoku solver layer,

- A neural network processes the Sudoku grid image, recognizing digits

- The recognized digits pass to a solver layer configured with Sudoku rules

- The solver layer finds a valid solution satisfying all constraints

- The final output is a complete, logically consistent Sudoku solution

This architecture combines the strength of neural networks in perception (recognizing digits) with the strength of symbolic solvers in logical reasoning (finding a valid Sudoku solution).

Representation Learning and the Grounding Problem

The central challenge in integrating neural networks with logical solvers lies in representation learning and grounding. Neural networks must learn to produce representations that are compatible with the symbolic, discrete reasoning performed by theory solvers.

This challenge is particularly difficult because SMT solvers fundamentally operate on discrete symbolic logic, which is inherently non-continuous and therefore not immediately compatible with the gradient-based optimization used in neural network training.

When the domain knowledge can be efficiently encoded and implemented, the perception problem still needs to be solved via learning. This proves challenging because solvers, in general, lack differentiability, and obtaining finely detailed training labels to supervise a suitable representation is often impractical. For example, annotating every possible constraint violation in complex reasoning tasks would require prohibitive human expert time, and might still miss subtle interactions between constraints.

We know how to encode logical rules for solvers, and we know how to train neural networks to recognize patterns. We could potentially bridge the gap by creating detailed training labels that teach the network exactly how to represent its outputs for the solver. However, creating such detailed annotations would be extremely time-consuming and expensive in practice. In a Visual Sudoku solver, we would need to annotate not just digit labels but exact bit-level representations, specific constraint violations, and reasoning paths for thousands of examples—a prohibitively expensive process.

Some key questions in addressing the grounding problem include:

- How do we map from the continuous outputs of neural networks to the discrete inputs expected by solvers?

- How do we backpropagate through this mapping to train neural networks?

- How do we ensure neural networks learn representations useful for solvers?

Small changes in continuous network outputs can lead to completely different discrete representations, creating a highly non-smooth optimization landscape that’s difficult to navigate using standard gradient-based methods.

This challenge is known as the grounding problem , and previous efforts have aimed to address it by:

- Either seeking a differentiable approximation for specific solver types

- Or identifying specialized differentiable logics for encoding domain knowledge

However, in both cases, the expressive capability of the solver layer is constrained to expressions that can ultimately be differentiated, albeit approximately.

Overcoming the Differentiability Challenge

Problem Statement

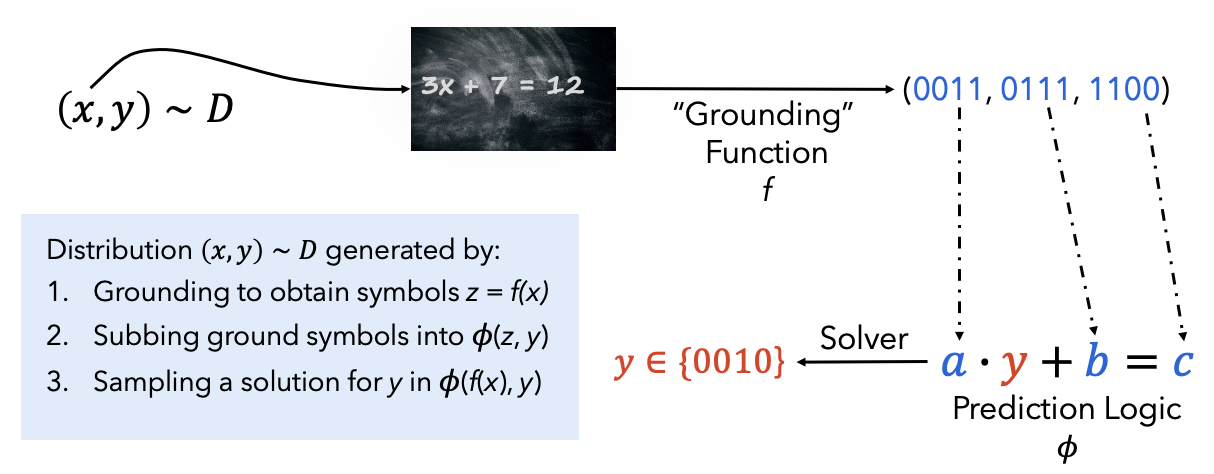

Before diving into specific techniques, let’s formalize the problem. We are solving a supervised learning problem using a dataset $$D = {(x_i, y_i)}_{i=1}^{N}$$

of \(N\) data points, trying to find parameters \(\theta\) of a function \(f(x;\theta)\) that minimize a loss \(L(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^N \ell(f(x_i;\theta), y_i)\). In our case, \(f\) includes a non-differentiable SMT solver component, making gradient-based optimization challenging.

Several approaches have been developed to address this differentiability challenge:

1. Surrogate Loss Functions

One approach creates differentiable approximations of logical constraints using surrogate loss functions:

$$L_{soft}(X) = \sum_{i=1}^{m} \text{ReLU}\left(\phi_i(X)\right)$$

Where \(\phi_i(X)\) represents constraint violation for clause \(i\) in input \(X\), where X represents the input to the surrogate loss function, typically network activations or predictions. ReLU imposes a penalty proportional to the violation degree. This ReLU function creates a one-sided penalty that only activates when constraints are violated. \(\phi_i\) are fixed based on the problem definition, and are defined by the specific problem structure.

For example, in Sudoku we could enforce that each row contains unique digits with:

$$\phi(r,d) = \text{ReLU}\left(\Big|\sum_c p(r,c,d) - 1\Big|\right)$$

This is 0 when the constraint is satisfied and positive when violated, with the magnitude indicating the violation degree.

In this formula, \(\phi(r,d)\) is the constraint violation function for row \(r\) and digit \(d\). The term \(p(r,c,d)\) represents the probability that cell \((r,c)\) contains digit \(d\) according to the network’s output. We sum these probabilities across all columns \(c\) in row \(r\). In a valid Sudoku solution, each digit appears exactly once per row, so this sum should equal 1. The absolute difference \(|\sum_c p(r,c,d) - 1|\) measures deviation from this constraint, and ReLU ensures we only penalize violations.

2. Relaxation of Boolean Logic

Another technique involves relaxing strict boolean values to continuous values in [0,1]:

- Logical AND: \(A \wedge B \approx A \cdot B\)

- Logical OR: \(A \vee B \approx 1 - (1-A)(1-B)\)

- Logical NOT: \(\neg A \approx 1-A\)

This makes logical operations compatible with gradient-based optimization.[1]

3. Differentiable Approximation of Projection Operations

This method transforms neural network outputs into a feasible region satisfying SMT constraints:

$$X_{t+1} = X_t - \eta\nabla L(X_t) + \lambda P_{feas}(X_t)$$

\(P_{feas}\) is a differentiable approximation of the projection operator mapping a point onto the feasible set defined by SMT constraints.

In this equation, \(X_t\) represents the current network output, \(\nabla L(X_t)\) is the gradient of the loss function, and \(\eta\) is the learning rate for standard gradient descent. The term \(P_{feas}(X_t)\) is a differentiable approximation of the projection operator that maps the current point onto the feasible set defined by the SMT constraints, with \(\lambda\) controlling the strength of this projection. This approach gradually guides the network toward outputs that satisfy logical constraints while maintaining differentiability throughout the optimization process. Prior work uses blackbox implementations of combinatorial solvers with linear objective functions to approximate gradients through these solvers.[2]

4. Differentiable Penalty Learning

Here, the SMT solver determines the feasibility of the neural network’s output during training, and based on this assessment, a penalty term is added to the loss function:

$$\frac{\partial L_{total}}{\partial W} = \frac{\partial L_{task}}{\partial W} + \lambda\frac{\partial L_{soft}}{\partial W}$$

\(L_{total}\) represents the combined loss function being minimized during training, and \(W\) represents the neural network parameters. The term \(\frac{\partial L_{task}}{\partial W}\) is the gradient of the task-specific loss (e.g., classification error), while \(\frac{\partial L_{soft}}{\partial W}\) is the gradient of a surrogate loss that encourages satisfaction of SMT constraints. The hyperparameter \(\lambda\) controls the relative importance of logical consistency versus task performance.

5. Logic-Driven Layer Incorporation

Special layers can be designed to mimic logical functions in a differentiable manner, embedding SMT-like logic without relying on a non-differentiable solver.[3]

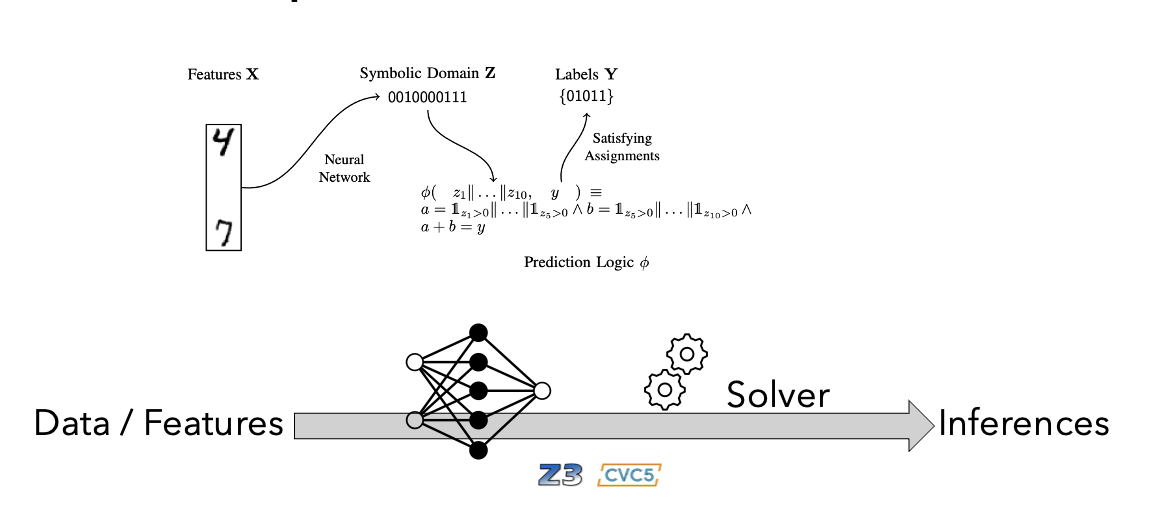

Our Approach: the SMTLayer

Our research introduces SMTLayer, a novel approach to integrating SMT solvers with neural networks. SMTLayer operates by:

- Forward Pass : Binarizing network activations and interpreting them as Boolean variables for the SMT solver

- Backward Pass : Using unsatisfiable cores to provide counterfactual information for gradient computation

In our paper, we present a solver layer incorporating the complete expressivity of SMT solvers. This SMT layer supports theories across categorical, numeric, string-based, and relational domains, making it expressive enough for a wide range of knowledge. We can leverage industry-standard solvers like Z3 and CVC5.

The SMTLayer operates as follows:

- Input passes through standard neural network layers producing a feature representation \(z\)

- During the forward pass, outputs from the previous layer map to designated free variables

- The SMT layer checks the satisfiability of the formula by substituting these ground terms for variables

- If the formula is satisfiable, the output consists of the solver’s model; if not satisfiable, the output defaults to zero

The main innovation lies in the backward pass, which uses unsatisfiable cores from the SMT solver to guide gradient computation.

Unsatisfiable Cores for Gradient Estimation

An unsatisfiable core is a subset of constraints that cannot be simultaneously satisfied. We use unsatisfiable cores to identify which inputs need modification to make the desired output feasible:

- We compute a target output \(y’\) that would reduce the loss

- We find the minimal subset of inputs inconsistent with this target output

- We adjust only these inputs, focusing gradient updates where they matter most

The process for computing the gradient using unsatisfiable cores:

- Calculate \(y’\) by adjusting the sign of the original output based on the loss gradient: $$ y’ = \text{sign}(y) - 2 \cdot \text{sign}\left(\frac{\partial L}{\partial y}\right) $$

In this equation, \(y\) is the original output from the SMT layer, \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial y}\) is the gradient of the loss with respect to this output, and \(\text{sign}()\) extracts just the sign (+1 or -1) of its argument. This calculation creates a new target output that would reduce the loss.

-

Determine if the current inputs \(z\) are consistent with this adjusted output \(y’\) by checking if the logical formula \(\phi(z,y’)\) is satisfiable. This step uses the SMT solver to evaluate whether our desired output is logically consistent with the current inputs.

-

If inconsistent (i.e., \(\phi(z,y’)\) is unsatisfiable), identify the unsatisfiable core—the minimal subset of input variables that, together with \(y’\), cause the logical inconsistency. The SMT solver provides this as a set of indices corresponding to problematic input variables.

-

Construct a new input \(z’\) by selectively flipping the signs of only those elements found in the unsatisfiable core:

\( z’[i] = \begin{cases} z[i] & \text{if } i \notin \text{unsat\_core} \\ -z[i] & \text{if } i \in \text{unsat\_core} \end{cases} \)

This targeted modification addresses precisely the inputs that contribute to logical inconsistency.

- Compute the updated gradient as the difference between the original and adjusted input, scaled by the magnitude of the output gradient: $$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial z} = (z’ - z) \cdot \left|\frac{\partial L}{\partial y}\right| $$

Here, the term \((z’ - z)\) identifies the direction of change needed for logical consistency, while \(\left|\frac{\partial L}{\partial y}\right|\) scales this change according to the importance of the output for reducing the overall loss.

This provides several benefits:

- Focused constraint satisfaction updating only relevant inputs

- Direct integration with logical consistency

- Efficient constraint enforcement

- Semantic interpretability providing insights into model reasoning

- Handling hard constraints ensuring outputs satisfy critical requirements

Advantages of Unsatisfiable Core Method Over Surrogate Loss

The unsatisfiable core method identifies the specific subset of variables responsible for logical constraint unsatisfiability, enabling targeted updates. This contrasts with surrogate loss functions that apply general penalties for constraint violations without localizing specific issues.

With the unsatisfiable core method, logical constraints embed directly into the training process, ensuring each backward pass incorporates direct information about achieving constraint satisfiability. The method allows for minimal, necessary adjustments avoiding unnecessary changes to other parameters.

The method also provides interpretability by explicitly identifying which components cause constraint violation, offering insight into why certain outputs are logically inconsistent.

Experimental Results

We evaluated SMTLayer on tasks combining perception and reasoning:

- MNIST Addition : Recognizing and adding handwritten digits

- Visual Algebra : Solving algebraic equations from images

- Visual Sudoku : This requires first interpreting handwritten numbers, then solving the puzzle according to Sudoku rules

- Liar’s Puzzle : Solving logical puzzles about truth-telling

Visual Sudoku

This task involves completing a 9 × 9 Sudoku board where each entry is an MNIST digit. We used the dataset from the SATNet[1] evaluation and examined three configurations obtained by sampling 10%, 50%, and 100% of the original training set.

For Sudoku, SMTLayer’s accuracy assessment focused on the correctness of the entire board, not just individual cells. This is a strict evaluation criterion, as a single incorrect cell would make the entire solution wrong.

Liar’s Puzzle

The Liar’s Puzzle comprises three sentences spoken by three distinct agents: Alice, Bob, and Charlie. One of the agents is “guilty” of an unspecified offense, and in each sentence, the corresponding agent either states that one of the other parties is either guilty or innocent. For example, “Alice says that Bob is innocent.”

It is assumed that two of the agents are honest, and the guilty party is not honest. This creates a logical puzzle that requires reasoning about truth and falsehood. The logic has non-stratified occurrences of negation, so it cannot be encoded with some other approaches like Scallop[3].

We selected a training sample that does not fully specify the logic, so conventional training should be insufficient to identify a good model. This tests the model’s ability to learn complex logical relationships from limited examples.

Our results demonstrate that SMTLayer outperforms both conventional neural networks and prior solver-integrated approaches in terms of accuracy, training time, or both:

- Accuracy : 25% higher accuracy than SATNet[1] for Sudoku puzzles

- Robustness : Maintained 98% accuracy under new distributions (compared to 10% with SATNet[1])

- Efficiency : Approximately 4x faster than Scallop[3]

Our findings include:

- SMTLayer converges with significantly less training data than alternatives

- Models trained with SMTLayer show robustness to certain types of covariate shift related to the symbolic component

- SMTLayer is consistently faster than Scallop[3], though currently slower than SATNet[1] due to lack of GPU parallelization

Performance Analysis

| Configuration | Conventional | w/ SMTLayer | w/ SATNet | w/ Scallop |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNIST+ 10% | 10.0% | 98.1% | 10.0% | 33.7% |

| MNIST+ 25% | 32.5% | 98.3% | 34.2% | 65.8% |

| MNIST+ 100% | 98.3% | 98.5% | 96.7% | 98.6% |

| Vis. Alg. #1 | 24.1% | 98.2% | 19.6% | 18.7% |

| Liar’s Puzzle | 54.2% | 86.1% | 84.6% | — |

| Vis. Sudoku 10% | 0.0% | 66.0% | 0.0% | — |

| Vis. Sudoku 100% | 0.0% | 79.1% | 63.2% | — |

The most dramatic advantages appear in data-limited scenarios:

MNIST Addition : With only 10% of possible digit pairs in training, SMTLayer achieved 98% accuracy on all possible pairs, while baselines achieved only 10% accuracy.

Visual Algebra : When trained on equations with same-digit coefficients, SMTLayer correctly solved equations with mixed-digit coefficients at 98% accuracy. Standard neural networks showed only 24% accuracy when faced with new coefficient combinations.

Visual Sudoku : With only 10% of training data, SMTLayer achieved 66% accuracy on complete boards, whereas other approaches achieved 0%. Even with full training data, conventional networks failed while SMTLayer reached 79.1%.

Liar’s Puzzle : SMTLayer demonstrated 86.1% accuracy after seeing only a small subset of possible scenarios.

Computational Efficiency Considerations

Our current implementation is consistently faster than Scallop[3], and nearly 4× faster in the case of visual algebra. It is slower than SATNet[1] in some configurations due to the lack of GPU parallelization.

Future work could explore several avenues for improving computational efficiency:

GPU Acceleration: Developing GPU-compatible versions of SMT solvers or their interfaces Parallel Solving: Exploiting batch-level parallelism for multiple instances

Conclusion and Future Directions

SMTLayer demonstrates a promising approach to enhancing neural networks with logical reasoning capabilities. By integrating SMT solvers as neural network layers, we’ve created a framework that addresses several challenges.

- Bridging Perception and Reasoning : Combining pattern recognition strengths of neural networks with logical reasoning capabilities of symbolic methods

- Data Efficiency : Requiring less training data to achieve high performance

- Enhanced Robustness : Improving robustness to distribution shifts

- Interpretability by Design : Creating models where intermediate representations have clear semantic meaning

Practical implications extend to various domains, including:

- Automated code generation respecting language syntax and semantics

- Malware detection systems combining behavioral pattern recognition with rule-based signatures

- Security vulnerability analysis tools integrating code pattern detection with verification

- Intrusion detection systems reasoning across multiple data sources

- Threat intelligence platforms combining NLP with logical reasoning about attack patterns

Looking forward, we see connections with recent developments in large language models and AI agents. While LLMs have shown impressive capabilities, they still struggle with consistent logical reasoning. Approaches like SMTLayer could help address these limitations.

For AI agents making decisions in complex environments, SMTLayer offers a potential pathway to create agents that can both perceive their environment effectively and reason about it according to predefined rules and constraints.

Neurosymbolic approaches like SMTLayer represent a step toward AI systems that combine the flexibility and pattern recognition of neural networks with the precision and reliability of symbolic reasoning. By bridging these historically separate paradigms, we can create more capable, robust, and trustworthy AI systems.

This blog post is based on joint work with Zifan Wang, Kaiji Lu, Vijay Ganesh, Somesh Jha, and Matt Fredrikson.

References

[1] Wang, Po-Wei, et al. “Satnet: Bridging deep learning and logical reasoning using a differentiable satisfiability solver.” ICML 2019.

[2] Vlastelica, Marin, et al. “Differentiation of blackbox combinatorial solvers.” arXiv 2019.

[3] Li, Ziyang, et al. “Scallop: A language for neurosymbolic programming.” Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages 2023.