New Website Sheds Light on Privacy Policy Shortcomings, Paves Way for Semi-Automated Policy Summarization

Daniel TkacikFriday, March 11, 2016Print this page.

Few people read privacy policies. Studies have projected that it would take an average user more than 600 hours to read every privacy policy associated with every website they visited in one year. However, research conducted over the past two years by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University, Fordham University and Stanford University is paving the way to a day when technology may be able to provide users with short summaries of privacy policies.

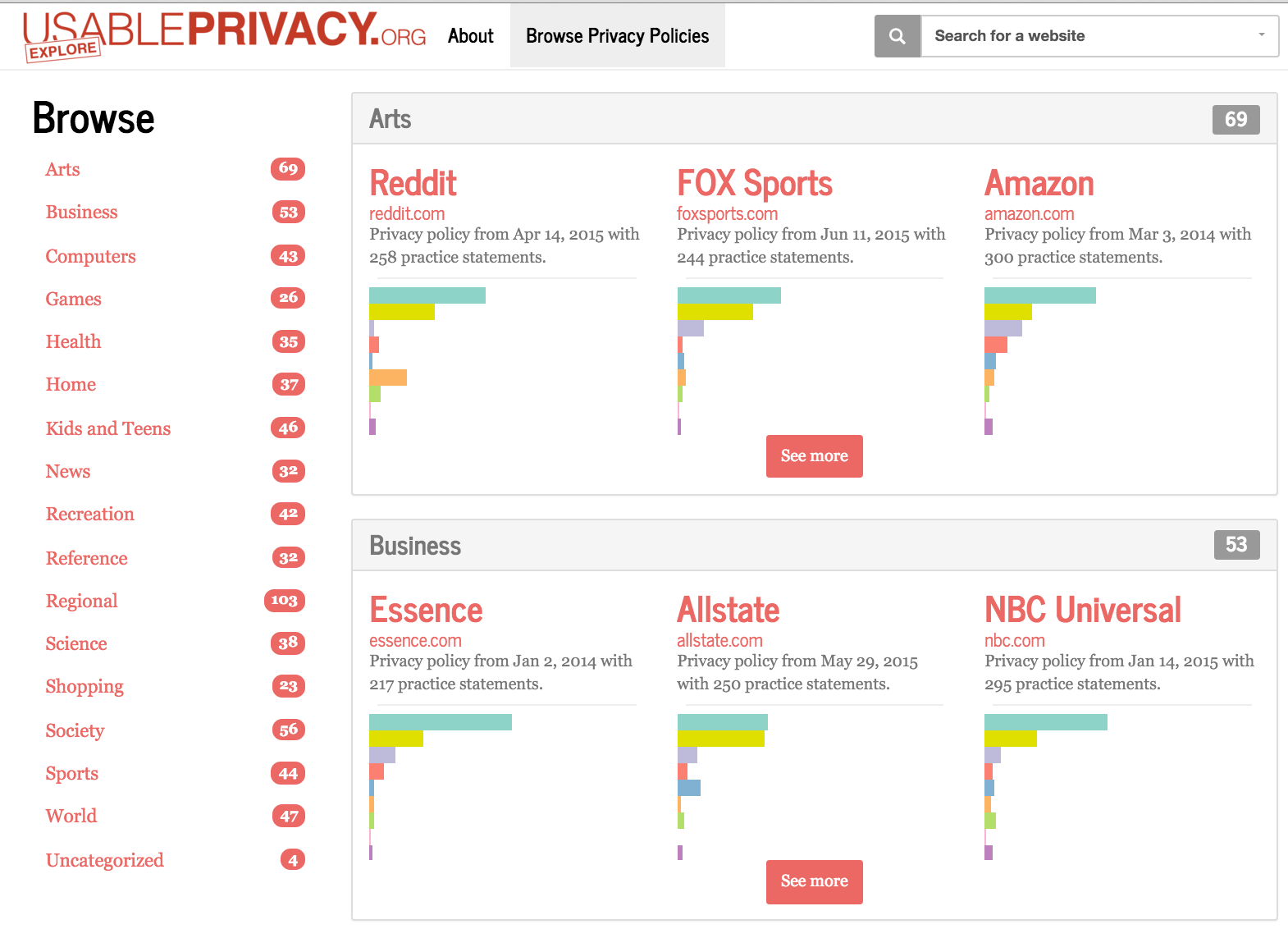

As part of an effort to share early results, the Usable Privacy Policy project has released a website that enables visitors to navigate more than 23,000 privacy policy annotations covering 193 websites. The project leverages crowdsourcing, machine learning and natural language processing to semi-automatically annotate privacy policies, extracting relevant statements from the often long and rather convoluted policies found on many websites and mobile apps today.

"This is the first site to provide analysis of privacy policies at this scale," said School of Computer Science Professor Norman Sadeh, lead principal investigator on the study and a researcher in Carnegie Mellon's CyLab security and privacy institute. "Our objective is to produce succinct yet informative summaries that can be included in browser plug-ins or interactively conveyed to users by privacy assistants that inform users about salient privacy practices."

In its current form, the Usable Privacy Policy website features interactive functionality that allows lay users to explore the content of a number of privacy policies. Color codes help users select from a menu of privacy practices that might interest them. For instance, a user interested in learning more about the data collected by a given site can select "first party collection practices" and all statements identified in the policy about data collection will be highlighted. Similarly, users can click the "third party sharing practices" option and see a display of statements made by the site about different entities with which it shares user data. The interactive tool covers a comprehensive number of different practices, including whether the site provides opt-out or opt-in choices for users, discloses its retention policy, includes statements about "Do Not Track" as mandated by California law (CalOPPA), and much more.

"While navigating our site, people will notice how complex and fragmented many privacy policies are," Sadeh said. "The vast majority of statements are about first-party collection and third-party sharing, and contain significant levels of ambiguity when it comes to determining exactly what is being collected and with whom it is shared."

The tool also gives each privacy policy a grade on reading level based on its language. Google's privacy policy, for example, is written on a Grade 13 (college) reading level. The privacy policy for Playstation.com, a site with a presumably large population of children and teen visitors, is written for grade 17 (college graduate) according to the tool.

"Color codes also make it clear that privacy policies tend to mix a variety of different statements in the same paragraph, often requiring the reader to read large portions of the policy, if not the entire policy, before hoping to be able to answer simple questions," added Professor Joel Reidenberg, the Fordham principal investigator on the project and director of the Fordham Center on Law and Information Policy. "Many sites hardly provide users with any real choices. Most policies that mention 'Do Not Track' do so by simply indicating that they do not handle Do Not Track requests — the bare minimum required under CalOPPA."

While the annotations on the website were crowdsourced from law students at Fordham University, the researchers say they're working toward automation.

"We are now using machine learning and natural language processing to semi-automate and hopefully one day fully automate, the analysis of privacy policies," says Sadeh.

The Usable Privacy Project is supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation. The website design team also included Institute for Software Research post-doctoral fellows Mads Schaarup Andersen, Florian Schaub and Shomir Wilson; Language Technologies Institute graduate student Aswarth Dara; and undergrad computer science freshman Sushain Cherivirala.

About Carnegie Mellon University CyLab:Carnegie Mellon University CyLab is a university-wide, multidisciplinary cybersecurity and privacy research institute. With over 50 core faculty, CyLab partners with industry and government to develop and test systems that lead to a world in which people can trust technology. CyLab stretches across five colleges encompassing the fields of engineering, computer science, business, public policy, information systems, humanities and social sciences.

About Fordham CLIP: the Fordham Center on Law and Information Policy is a research center based at Fordham University's School of Law that seeks to bring together scholars, attorneys, experts from the business, technology and policy communities, students, and the public to address and assess policies and solutions for cutting-edge issues that affect the evolution of the information economy. Fordham CLIP focuses on five related areas: law and policy relating to the regulation of information and public values; law and policy for innovation and knowledge creation; technology, privacy and security; technology and governance; and the protection of intellectual property and information assets.

Byron Spice | 412-268-9068 | bspice@cs.cmu.edu