As fake news stories continue to pepper social media pages, some companies are taking an active approach to banning the spread of misinformation. Facebook is focusing on the "worst of the worst" offenders and partner with outside fact-checkers and news organizations to sort honest news reports from made-up stories.

If enough people report a story as fake, Facebook will pass it to third-party fact-checking organizations that are part of the nonprofit Poynter Institute's International Fact-Checking Network.

Five fact-checking and news organizations are working with Facebook, including ABC News, the Associated Press, FactCheck.org, Politifact and Snopes. Facebook said this group is likely to expand.

The way fake news travels online is most often through social media and research shows the more followers an account has, the more credible people think it is.

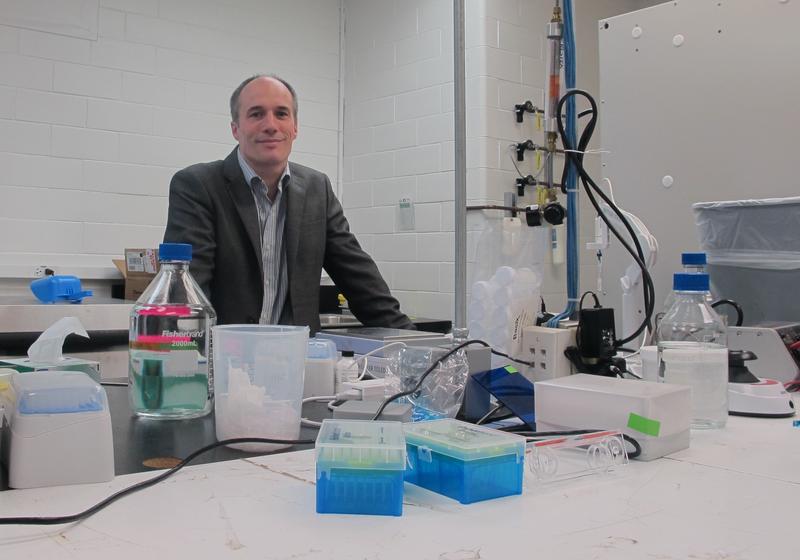

A paper published in Computers in Human Behavior details that idea and Carnegie Mellon University computer science professor Christos Faloutsos said fraudsters, or ghost accounts created to look like real Twitter or Facebook followers, compound the problem.

“So there are services that can make a lot of accounts to follow you so that the paying account looks important,” Faloutsos said.

For $10 a social media user can add 1,000 followers overnight. But Faloutsos and third-year grad students, Bryan Hooi and Hyun Ah Song, have come up with code they call “Fraudar.”

“If I follow you because you paid me, and I follow Bryan because he paid me and Hyun Ah … this creates a sub network that is very suspicious,” Faloutsos said.

Fraudar can assess the users of a social media outlet and find links, commonly referred to as a bipartite core, to target suspicious accounts.

“We call it camouflage,” said Faloutsos. “So these fake accounts will follow you and Bryan and Hyun Ah because you paid them but they can also follow President Obama, Donald Trump and Lady Gaga so that they look normal. The algorithm down plays the popular accounts and then the bipartite core is more obvious in that case.”

To get the algorithm right and prevent targeting legitimate accounts, Song said they went through several code changes.

Most social media outlets have policies forbidding fake accounts and followers, even shutting down fraudulent accounts. But fraudsters are often finding new ways to work around that, Faloutsos said.

“So there’s another project we are doing after approval from university lawyers,” Faloutsos said. “We are buying followers ourselves. We created some fake accounts and we pay these companies small amounts and they follow us.”

The team will use what they learn to try to stay one step ahead of the companies offering fake followers. Among the ideas is adding geographic data on the followers or time stamps on when they start to follow a given user.

Hooi said they hope to use the same technique to flag fake Amazon reviews, for instance if someone gives five star reviews to everything from children’s toys to airplane parts.

In this week’s Tech Headlines:

- Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh have been granted $1.7 million to work on mathematical models that could allow doctors to predict the best way to treat individual cystic fibrosis patients by looking at cells in their noses. The lung disease often eventually leads to respiratory failure. Pitt school of medicine associate professor Tim Corcoran said the researchers hope to show that nasal cell sampling and interpretation of the data by the computer models can lead to “a highly personalized approach to treating a patient with CF that could begin as early as birth.”

- The Obama administration has failed to renegotiate portions of an international arms control arrangement to make it easier to export tools related to hacking and surveillance software. The rare U.S. move to push for revisions to a 2013 rule was derailed at an annual meeting in Vienna, where officials from 41 countries that signed onto it were meeting. U.S. officials had wanted more precise language. Critics have argued that the current language, while well meaning, broadly sweeps up research tools and technologies used to thwart.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

(Photo via Hank Mitchell/Flickr)