Heidi

by Johanna Spyri

Illustrated By Jessie Willcox Smith

HEIDI Part 2

CHAPTER VII

FRAULEIN ROTTENMEIER SPENDS AN UNCOMFORTABLE DAY

When Heidi opened her eyes on her first morning in Frankfurt she

could not think where she was. Then she rubbed them and looked

about her. She was sitting up in a high white bed, on one side of

a large, wide room, into which the light was falling through

very, very long white curtains; near the window stood two chairs

covered with large flowers, and then came a sofa with the same

flowers, in front of which was a round table; in the corner was a

washstand, with things upon it that Heidi had never seen in her

life before. But now all at once she remembered that she was in

Frankfurt; everything that had happened the day before came back

to her, and finally she recalled clearly the instructions that

had been given her by the lady-housekeeper, as far as she had

heard them. Heidi jumped out of bed and dressed herself; then she

ran first to one window and then another; she wanted to see the

sky and country outside; she felt like a bird in a cage behind

those great curtains. But they were too heavy for her to put

aside, so she crept underneath them to get to the window. But

these again were so high that she could only just get her head

above the sill to peer out. Even then she could not see what she

longed for. In vain she went first to one and then the other of

the windows--she could see nothing but walls and windows and

again walls and windows. Heidi felt quite frightened. It was

still early, for Heidi was accustomed to get up early and run out

at once to see how everything was looking, if the sky was blue

and if the sun was already above the mountains, or if the fir

trees were waving and the flowers had opened their eyes. As a

bird, when it first finds itself in its bright new cage, darts

hither and thither, trying the bars in turn to see if it cannot

get through them and fly again into the open, so Heidi continued

to run backwards and forwards, trying to open first one and then

the other of the windows, for she felt she could not bear to see

nothing but walls and windows, and somewhere outside there must

be the green grass, and the last unmelted snows on the mountain

slopes, which Heidi so longed to see. But the windows remained

immovable, try what Heidi would to open them, even endeavoring to

push her little fingers under them to lift them up; but it was

all no use. When after a while Heidi saw that her efforts were

fruitless, she gave up trying, and began to think whether she

would not go out and round the house till she came to the grass,

but then she remembered that the night before she had only seen

stones in front of the house. At that moment a knock came to the

door, and immediately after Tinette put her head inside and said,

"Breakfast is ready." Heidi had no idea what an invitation so

worded meant, and Tinette's face did not encourage any

questioning on Heidi's part, but rather the reverse. Heidi was

sharp enough to read its expression, and acted accordingly. So

she drew the little stool out from under the table, put it in the

corner and sat down upon it, and there silently awaited what

would happen next. Shortly after, with a good deal of rustling

and bustling Fraulein Rottenmeier appeared, who again seemed very

much put out and called to Heidi, "What is the matter with you,

Adelheid? Don't you understand what breakfast is? Come along at

once!"

Heidi had no difficulty in understanding now and followed at

once. Clara had been some time at the breakfast table and she

gave Heidi a kindly greeting, her face looking considerably more

cheerful than usual, for she looked forward to all kinds of new

things happening again that day. Breakfast passed off quietly;

Heidi eat her bread and butter in a perfectly correct manner, and

when the meal was over and Clara wheeled back into the study,

Fraulein Rottenmeier told her to follow and remain with Clara

until the tutor should arrive and lessons begin.

As soon as the children were alone again, Heidi asked, "How can

one see out from here, and look right down on to the ground?"

"You must open the window and look out," replied Clara amused.

"But the windows won't open," responded Heidi sadly.

"Yes, they will," Clara assured her. "You cannot open them, nor I

either, but when you see Sebastian you can ask him to open one."

It was a great relief to Heidi to know that the windows could be

opened and that one could look out, for she still felt as if she

was shut up in prison. Clara now began to ask her questions about

her home, and Heidi was delighted to tell her all about the

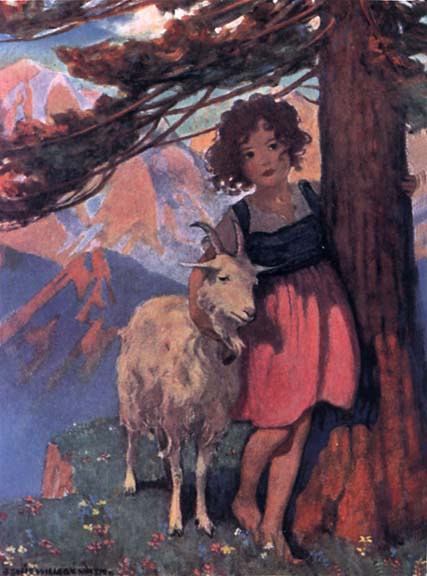

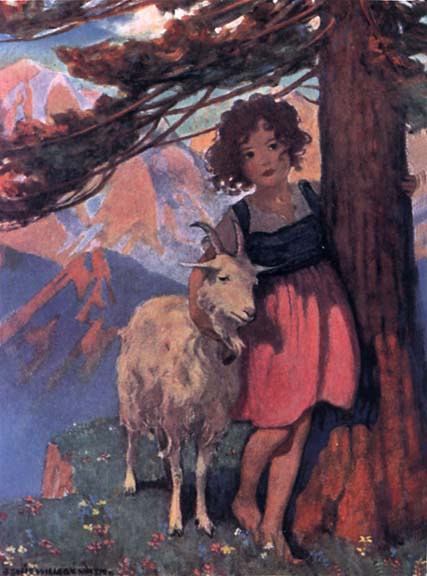

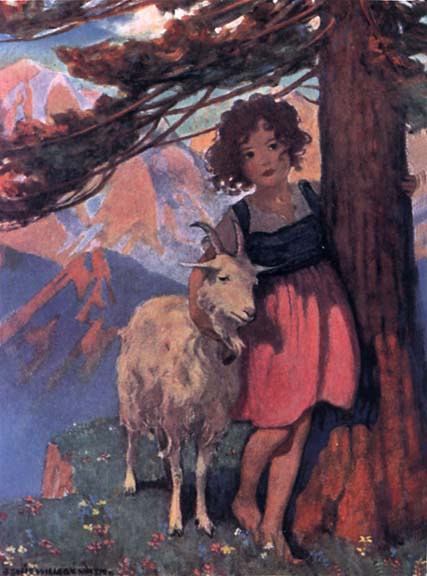

mountain and the goats, and the flowery meadows which were so

dear to her.

Meanwhile her tutor had arrived; Fraulein Rottenmeier, however,

did not bring him straight into the study but drew him first

aside into the dining-room, where she poured forth her troubles

and explained to him the awkward position in which she was

placed, and how it had all come about. It appeared that she had

written some time back to Herr Sesemann to tell him that his

daughter very much wished to have a companion, and had added how

desirable she thought it herself, as it would be a spur to Clara

at her lessons and an amusement for her in her playtime. Fraulein

Rottenmeier had privately wished for this arrangement on her own

behalf, as it would relieve her from having always to entertain

the sick girl herself, which she felt at times was too much for

her. The father had answered that he was quite willing to let his

daughter have a companion, provided she was treated in every way

like his own child, as he would not have any child tormented or

put upon which was a very unnecessary remark," put in Fraulein

Rottenmeier, "for who wants to torment children!" But now she

went on to explain how dreadfully she had been taken in about the

child, and related all the unimaginable things of which she had

already been guilty, so that not only would he have to begin with

teaching her the A B C, but would have to start with the most

rudimentary instruction as regarded everything to do with daily

life. She could see only one way out of this disastrous state of

affairs, and that was for the tutor to declare that it was

impossible for the two to learn together without detriment to

Clara, who was so far ahead of the other; that would be a valid

excuse for getting rid of the child, and Herr Sesemann would be

sure to agree to the child being sent home again, but she dared

not do this without his order, since he was aware that by this

time the companion had arrived. But the tutor was a cautious man

and not inclined to take a partial view of matters. He tried to

calm Fraulein Rottenmeier, and gave it as his opinion that if the

little girl was backward in some things she was probably advanced

in others, and a little regular teaching would soon set the

balance right. When Fraulein Rottenmeier saw that he was not

ready to support her, and evidently quite ready to undertake

teaching the alphabet, she opened the study door, which she

quickly shut again as soon as he had gone through, remaining on

the other side herself, for she had a perfect horror of the A B

C. She walked up and down the dining-room, thinking over in her

own mind how the servants were to be told to address Adelaide.

The father had written that she was to be treated exactly like

his own daughter, and this would especially refer, she imagined,

to the servants. She was not allowed, however, a very long

interval of time for consideration, for suddenly the sound of a

frightful crash was heard in the study, followed by frantic cries

for Sebastian. She rushed into the room. There on the floor lay

in a confused heap, books, exercise-books, inkstand, and other

articles with the table-cloth on the top, while from beneath them

a dark stream of ink was flowing all across the floor. Heidi had

disappeared.

"Here's a state of things!" exclaimed Fraulein Rottenmeier,

wringing her hands. "Table-cloth, books, work-basket, everything

lying in the ink! It was that unfortunate child, I suppose!"

The tutor was standing looking down at the havoc in distress;

there was certainly only one view to be taken of such a matter as

this and that an unfavorable one. Clara meanwhile appeared to

find pleasure in such an unusual event and in watching the

results. "Yes, Heidi did it," she explained, "but quite by

accident; she must on no account be punished; she jumped up in

such violent haste to get away that she dragged the tablecloth

along with her, and so everything went over. There were a number

of vehicles passing, that is why she rushed off like that;

perhaps she has never seen a carriage."

"Is it not as I said? She has not the smallest notion about

anything! not the slightest idea that she ought to sit still and

listen while her lessons are going on. But where is the child who

has caused all this trouble? Surely she has not run away! What

would Herr Sesemann say to me?" She ran out of the room and down

the stairs. There, at the bottom, standing in the open door-way,

was Heidi, looking in amazement up and down the street.

"What are you doing? What are you thinking of to run away like

that?" called Fraulein Rottenmeier.

"I heard the sound of the fir trees, but I cannot see where they

are, and now I cannot hear them any more," answered Heidi,

looking disappointedly in the direction whence the noise of the

passing carriages had reached her, and which to Heidi had seemed

like the blowing of the south wind in the trees, so that in great

joy of heart she had rushed out to look at them.

"Fir trees! do you suppose we are in a wood? What ridiculous

ideas are these? Come upstairs and see the mischief you have

done!"

Heidi turned and followed Fraulein Rottenmeier upstairs; she was

quite astonished to see the disaster she had caused, for in her

joy and haste to get to the fir trees she had been unaware of

having dragged everything after her.

"I excuse you doing this as it is the first time, but do not let

me know you doing it a second time," said Fraulein Rottenmeier,

pointing to the floor. "During your lesson time you are to sit

still and attend. If you cannot do this I shall have to tie you

to your chair. Do you understand?"

"Yes," replied Heidi, "but I will certainly not move again," for

now she understood that it was a rule to sit still while she was

being taught.

Sebastian and Tinette were now sent for to clear up the broken

articles and put things in order again; the tutor said

good-morning and left, as it was impossible to do any more

lessons that day; there had been certainly no time for gaping

this morning.

Clara had to rest for a certain time during the afternoon, and

during this interval, as Fraulein Rottenmeier informed Heidi, the

latter might amuse herself as she liked. When Clara had been

placed on her couch after dinner, and the lady-housekeeper had

retired to her room, Heidi knew that her time had come to choose

her own occupation. It was just what she was longing for, as

there was something she had made up her mind to do; but she would

require some help for its accomplishment, and in view of this she

took her stand in the hall in front of the dining-room door in

order to intercept the person she wanted. In a few minutes up

came Sebastian from the kitchen with a tray of silver tea-things,

which he had to put away in the dining-room cupboard. As he

reached the top stairs Heidi went up to him and addressed him in

the formal manner she had been ordered to use by Fraulein

Rottenmeier.

Sebastian looked surprised and said somewhat curtly, "What is it

you want, miss?"

"I only wished to ask you something, but it is nothing bad like

this morning," said Heidi, anxious to conciliate him, for she saw

that Sebastian was rather in a cross temper, and quite thought

that it was on account of the ink she had spilt on the floor.

"Indeed, and why, I should first like to know, do you address me

like that?" replied Sebastian, evidently still put out.

"Fraulein Rottenmeier told me always to speak to you like that,"

said Heidi.

Then Sebastian laughed, which very much astonished Heidi, who had

seen nothing amusing in the conversation, but Sebastian, now he

understood that the child was only obeying orders, added in a

friendly voice, "What is it then that miss wants?"

It was now Heidi's turn to be a little put out, and she said, "My

name is not miss, it is Heidi."

"Quite so, but the same lady has ordered me to call you miss,"

explained Sebastian.

"Has she? oh, then I must be called so," said Heidi submissively,

for she had already noticed that whatever Fraulein Rottenmeier

said was law. "Then now I have three names," she added with a

sigh.

"What was it little miss wished to ask?" said Sebastian as he

went on into the dining-room to put away his silver.

"How can a window be opened?"

"Why, like that!" and Sebastian flung up one of the large

windows.

Heidi ran to it, but she was not tall enough to see out, for her

head only reached the sill.

"There, now miss can look out and see what is going on below,"

said Sebastian as he brought her a high wooden stool to stand on.

Heidi climbed up, and at last, as she thought, was going to see

what she had been longing for. But she drew back her head with a

look of great disappointment on her face.

"Why, there is nothing outside but the stony streets," she said

mournfully; "but if I went right round to the other side of the

house what should I see there, Sebastian?"

"Nothing but what you see here," he told her.

"Then where can I go to see right away over the whole valley?"

"You would have to climb to the top of a high tower, a church

tower, like that one over there with the gold ball above it. From

there you can see right away ever so far."

Heidi climbed down quickly from her stool, ran to the door, down

the steps and out into the street. Things were not, however,

quite so easy as she thought. Looking from the window the tower

had appeared so close that she imagined she had only to run over

the road to reach it. But now, although she ran along the whole

length of the street, she still did not get any nearer to it, and

indeed soon lost sight of it altogether; she turned down another

street, and went on and on, but still no tower. She passed a

great many people, but they all seemed in such a hurry that Heidi

thought they had not time to tell her which way to go. Then

suddenly at one of the street corners she saw a boy standing,

carrying a hand-organ on his back and a funny-looking animal on

his arm. Heidi ran up to him and said, Where is the tower with

the gold ball on the top?"

"I don't know," was the answer.

"Who can I ask to show me?" she asked again.

"I don't know."

"Do you know any other church with a high tower?"

"Yes, I know one."

"Come then and show it me."

"Show me first what you will give me for it," and the boy held

out his hand as he spoke. Heidi searched about in her pockets and

presently drew out a card on which was painted a garland of

beautiful red roses; she looked at it first for a moment or two,

for she felt rather sorry to part with it; Clara had only that

morning made her a present of it--but then, to look down into the

valley and see all the lovely green slopes! "There," said Heidi,

holding out the card, "would you like to have that?"

The boy drew back his hand and shook his head.

"What would you like then?" asked Heidi, not sorry to put the

card back in her pocket.

"Money."

"I have none, but Clara has; I am sure she will give me some; how

much do you want?"

"Twopence."

"Come along then."

They started off together along the street, and on the way Heidi

asked her companion what he was carrying on his back; it was a

hand-organ, he told her, which played beautiful music when he

turned the handle. All at once they found themselves in front of

an old church with a high tower; the boy stood still, and said,

"There it is."

"But how shall I get inside?" asked Heidi, looking at the fast

closed doors.

"I don't know," was the answer.

"Do you think that I can ring as they do for Sebastian?"

"I don't know."

Heidi had by this time caught sight of a bell in the wall which

she now pulled with all her might. "If I go up you must stay down

here, for I do not know the way back, and you will have to show

me."

"What will you give me then for that?"

"What do you want me to give you?"

"Another twopence."

They heard the key turning inside, and then some one pulled open

the heavy creaking door; an old man came out and at first looked

with surprise and then in anger at the children, as he began

scolding them: "What do you mean by ringing me down like this?

Can't you read what is written over the bell, 'For those who wish

to go up the tower'?"

The boy said nothing but pointed his finger at Heidi. The latter

answered, "But I do want to go up the tower."

"What do you want up there?" said the old man. Has somebody sent

you?"

"No," replied Heidi, "I only wanted to go up that I might look

down."

"Get along home with you and don't try this trick on me again, or

you may not come off so easily a second time," and with that he

turned and was about to shut the door. But Heidi took hold of his

coat and said beseechingly, "Let me go up, just once."

He looked around, and his mood changed as he saw her pleading

eyes; he took hold of her hand and said kindly, "Well, if you

really wish it so much, I will take you."

The boy sat down on the church steps to show that he was content

to wait where he was.

Hand in hand with the old man Heidi went up the many steps of the

tower; they became smaller and smaller as they neared the top,

and at last came one very narrow one, and there they were at the

end of their climb. The old man lifted Heidi up that she might

look out of the open window.

"There, now you can look down," he said.

Heidi saw beneath her a sea of roofs, towers, and chimney-pots;

she quickly drew back her head and said in a sad, disappointed

voice, "It is not at all what I thought."

"You see now, a child like you does not understand anything about

a view! Come along down and don't go ringing at my bell again!"

He lifted her down and went on before her down the narrow

stairway. To the left of the turn where it grew wider stood the

door of the tower-keeper's room, and the landing ran out beside

it to the edge of the steep slanting roof. At the far end of this

was a large basket, in front of which sat a big grey cat, that

snarled as it saw them, for she wished to warn the passers-by

that they were not to meddle with her family. Heidi stood still

and looked at her in astonishment, for she had never seen such a

monster cat before; there were whole armies of mice, however, in

the old tower, so the cat had no difficulty in catching half a

dozen for her dinner every day. The old man seeing Heidi so

struck with admiration said, "She will not hurt you while I am

near; come, you can have a peep at the kittens."

Heidi went up to the basket and broke out into expressions of

delight.

"Oh, the sweet little things! the darling kittens," she kept on

saying, as she jumped from side to side of the basket so as, not

to lose any of the droll gambols of the seven or eight little

kittens that were scrambling and rolling and falling over one

another.

"Would you like to have one?" said the old man, who enjoyed

watching the child's pleasure.

"For myself to keep?" said Heidi excitedly, who could hardly

believe such happiness was to be hers.

"Yes, of course, more than one if you like--in short, you can

take away the whole lot if you have room for them," for the old

man was only too glad to think he could get rid of his kittens

without more trouble.

Heidi could hardly contain herself for joy. There would be plenty

of room for them in the large house, and then how astonished and

delighted Clara would be when she saw the sweet little kittens.

"But how can I take them with me?" asked Heidi, and was going

quickly to see how many she could carry away in her hands, when

the old cat sprang at her so fiercely that she shrank back in

fear.

"I will take them for you if you will tell me where," said the

old man, stroking the cat to quiet her, for she was an old friend

of his that had lived with him in the tower for many years.

"To Herr Sesemann's, the big house where there is a gold dog's

head on the door, with a ring in its mouth," explained Heidi.

Such full directions as these were not really needed by the old

man, who had had charge of the tower for many a long year and

knew every house far and near, and moreover Sebastian was an

acquaintance of his.

"I know the house," he said, "but when shall I bring them, and

who shall I ask for?--you are not one of the family, I am sure."

"No, but Clara will be so delighted when I take her the kittens."

The old man wished now to go downstairs, but Heidi did not know

how to tear herself away from the amusing spectacle.

"If I could just take one or two away with me! one for myself and

one for Clara, may I?"

"Well, wait a moment," said the man, and he drew the cat

cautiously away into his room, and leaving her by a bowl of food

came out again and shut the door. "Now take two of them."

Heidi's eyes shone with delight. She picked up a white kitten and

another striped white and yellow, and put one in the right, the

other in the left pocket. Then she went downstairs. The boy was

still sitting outside on the steps, and as the old man shut the

door of the church behind them, she said, "Which is our way to

Herr Sesemann's house?"

"I don't know," was the answer.

Heidi began a description of the front door and the steps and the

windows, but the boy only shook his head, and was not any the

wiser.

"Well, look here," continued Heidi, "from one window you can see

a very, very large grey house, and the roof runs like this--" and

Heidi drew a zigzag line in the air with her forefinger.

With this the boy jumped up, he was evidently in the habit of

guiding himself by similar landmarks. He ran straight off with

Heidi after him, and in a very short time they had reached the

door with the large dog's head for the knocker. Heidi rang the

bell. Sebastian opened it quickly, and when he saw it was Heidi,

"Make haste! make haste," he cried in a hurried voice.

Heidi sprang hastily in and Sebastian shut the door after her,

leaving the boy, whom he had not noticed, standing in wonder on

the steps.

"Make haste, little miss," said Sebastian again; "go straight

into the dining-room, they are already at table; Fraulein

Rottenmeier looks like a loaded cannon. What could make the

little miss run off like that?"

Heidi walked into the room. The lady housekeeper did not look up,

Clara did not speak; there was an uncomfortable silence.

Sebastian pushed her chair up for her, and when she was seated

Fraulein Rottenmeier, with a severe countenance, sternly and

solemnly addressed her: "I will speak with you afterwards,

Adelheid, only this much will I now say, that you behaved in a

most unmannerly and reprehensible way by running out of the house

as you did, without asking permission, without any one knowing a

word about it; and then to go wandering about till this hour; I

never heard of such behavior before."

"Miau!" came the answer back.

This was too much for the lady's temper; with raised voice she

exclaimed, "You dare, Adelheid, after your bad behavior, to

answer me as if it were a joke?"

"I did not--" began Heidi--"Miau! miau!"

Sebastian almost dropped his dish and rushed out of the room.

"That will do," Fraulein Rottenmeier tried to say, but her voice

was almost stifled with anger. "Get up and leave the room."

Heidi stood up frightened, and again made an attempt to explain.

"I really did not--" "Miau! miau! miau!"

"But, Heidi," now put in Clara, "when you see that it makes

Fraulein Rottenmeier angry, why do you keep on saying miau?"

"It isn't I, it's the kittens," Heidi was at last given time to

say.

"How! what! kittens!" shrieked Fraulein Rottenmeier. "Sebastian!

Tinette! Find the horrid little things! take them away!" And she

rose and fled into the study and locked the door, so as to make

sure that she was safe from the kittens, which to her were the

most horrible things in creation.

Sebastian was obliged to wait a few minutes outside the door to

get over his laughter before he went into the room again. He had,

while serving Heidi, caught sight of a little kitten's head

peeping out of her pocket, and guessing the scene that would

follow, had been so overcome with amusement at the first miaus

that he had hardly been able to finish handing the dishes. The

lady's distressed cries for help had ceased before he had

sufficiently regained his composure to go back into the

dining-room. It was all peace and quietness there now, Clara had

the kittens on her lap, and Heidi was kneeling beside her, both

laughing and playing with the tiny, graceful little animals.

"Sebastian," exclaimed Clara as he came in, "you must help us;

you must find a bed for the kittens where Fraulein Rottenmeier

will not spy them out, for she is so afraid of them that she will

send them away at once; but we want to keep them, and have them

out whenever we are alone. Where can you put them?"

"I will see to that," answered Sebastian willingly. "I will make

a bed in a basket and put it in some place where the lady is not

likely to go; you leave it to me." He set about the work at once,

sniggling to himself the while, for he guessed there would be a

further rumpus about this some day, and Sebastian was not without

a certain pleasure in the thought of Fraulein Rottenmeier being a

little disturbed.

Not until some time had elapsed, and it was nearing the hour for

going to bed, did Fraulein Rottenmeier venture to open the door a

crack and call through, "Have you taken those dreadful little

animals away, Sebastian?"

He assured her twice that he had done so; he had been hanging

about the room in anticipation of this question, and now quickly

and quietly caught up the kittens from Clara's lap and

disappeared with them.

The castigatory sermon which Fraulein Rottenmeier had held in

reserve for Heidi was put off till the following day, as she felt

too exhausted now after all the emotions she had gone through of

irritation, anger, and fright, of which Heidi had unconsciously

been the cause. She retired without speaking, Clara and Heidi

following, happy in their minds at knowing that the kittens were

lying in a comfortable bed.

CHAPTER VIII

THERE IS GREAT COMMOTION IN THE LARGE HOUSE

Sebastian had just shown the tutor into the study on the

following morning when there came another and very loud ring at

the bell, which Sebastian ran quickly to answer. "Only Herr

Sesemann rings like that," he said to himself; "he must have

returned home unexpectedly." He pulled open the door, and there

in front of him he saw a ragged little boy carrying a hand-organ

on his back.

"What's the meaning of this?" said Sebastian angrily. "I'll teach

you to ring bells like that! What do you want here?"

"I want to see Clara," the boy answered.

"You dirty, good-for-nothing little rascal, can't you be polite

enough to say 'Miss Clara'? What do you want with her?" continued

Sebastian roughly. She owes me fourpence," explained the boy.

"You must be out of your mind! And how do you know that any young

lady of that name lives here?"

"She owes me twopence for showing her the way there, and twopence

for showing her the way back."

"See what a pack of lies you are telling! The young lady never

goes out, cannot even walk; be off and get back to where you came

from, before I have to help you along."

But the boy was not to be frightened away; he remained standing,

and said in a determined voice, "But I saw her in the street, and

can describe her to you; she has short, curly black hair, and

black eyes, and wears a brown dress, and does not talk quite like

we do."

"Oho!" thought Sebastian, laughing to himself, "the little miss

has evidently been up to more mischief." Then, drawing the boy

inside he said aloud, "I understand now, come with me and wait

outside the door till I tell you to go in. Be sure you begin

playing your, organ the instant you get inside the room; the lady

is very fond of music."

Sebastian knocked at the study door, and a voice said, "Come in."

"There is a boy outside who says he must speak to Miss Clara

herself," Sebastian announced.

Clara was delighted at such an extraordinary and unexpected

message.

"Let him come in at once," replied Clara; "he must come in, must

he not," she added, turning to her tutor, "if he wishes so

particularly to see me?"

The boy was already inside the room, and according to Sebastian's

directions immediately began to play his organ. Fraulein

Rottenmeier, wishing to escape the A B C, had retired with her

work to the dining-room. All at once she stopped and listened.

Did those sounds come up from the street? And yet they seemed so

near! But how could there be an organ playing in the study? And

yet--it surely was so. She rushed to the other end of the long

dining-room and tore open the door. She could hardly believe her

eyes. There, in the middle of the study, stood a ragged boy

turning away at his organ in the most energetic manner. The tutor

appeared to be making efforts to speak, but his voice could not

be heard. Both children were listening delightedly to the music.

"Leave off! leave off at once!" screamed Fraulein Rottenmeier.

But her voice was drowned by the music. She was making a dash for

the boy, when she saw something on the ground crawling towards

her feet--a dreadful dark object--a tortoise. At this sight she

jumped higher than she had for many long years before, shrieking

with all her might, "Sebastian! Sebastian!"

The organ-player suddenly stopped, for this time her voice had

risen louder than the music. Sebastian was standing outside bent

double with laughter, for he had been peeping to see what was

going on. By the time he entered the room Fraulein Rottenmeier

had sunk into a chair.

"Take them all out, boy and animal! Get them away at once!" she

commanded him.

Sebastian pulled the boy away, the latter having quickly caught

up the tortoise, and when he had got him outside he put something

into his hand. "There is the fourpence from Miss Clara, and

another fourpence for the music. You did it all quite right!" and

with that he shut the front door upon him.

Quietness reigned again in the study, and lessons began once

more; Fraulein Rottenmeier now took up her station in the study

in order by her presence to prevent any further dreadful

goings-on.

But soon another knock came to the door, and Sebastian again

stepped in, this time to say that some one had brought a large

basket with orders that it was to be given at once to Miss Clara.

"For me?" said Clara in astonishment, her curiosity very much

excited, "bring it in at once that I may see what it is like."

Sebastian carried in a large covered basket and retired.

"I think the lessons had better be finished first before the

basket is unpacked," said Fraulein Rottenmeier.

Clara could not conceive what was in it, and cast longing glances

towards it. In the middle of one of her declensions she suddenly

broke off and said to the tutor, "Mayn't I just give one peep

inside to see what is in it before I go on?"

"On some considerations I am for it, on others against it," he

began in answer; "for it, on the ground that if your whole

attention is directed to the basket--" but the speech remained

unfinished. The cover of the basket was loose, and at this moment

one, two, three, and then two more, and again more kittens came

suddenly tumbling on to the floor and racing about the room in

every direction, and with such indescribable rapidity that it

seemed as if the whole room was full of them. They jumped over

the tutor's boots, bit at his trousers, climbed up Fraulein

Rottenmeier's dress, rolled about her feet, sprang up on to

Clara's couch, scratching, scrambling, and mewing: it was a sad

scene of confusion. Clara, meanwhile, pleased with their gambols,

kept on exclaiming, "Oh, the dear little things! how pretty they

are! Look, Heidi, at this one; look, look, at that one over

there!" And Heidi in her delight kept running after them first

into one corner and then into the other. The tutor stood up by

the table not knowing what to do, lifting first his right foot

and then his left to get it away from the scrambling, scratching

kittens. Fraulein Rottenmeier was unable at first to speak at

all, so overcome was she with horror, and she did not dare rise

from her chair for fear that all the dreadful little animals

should jump upon her at once. At last she found voice to call

loudly, Tinette! Tinette! Sebastian! Sebastian!"

They came in answer to her summons and gathered up the kittens,

by degrees they got them all inside the basket again and then

carried them off to put with the other two.

To-day again there had been no opportunity for gaping. Late that

evening, when Fraulein Rottenmeier had somewhat recovered from

the excitement of the morning, she sent for the two servants, and

examined their closely concerning the events of the morning. And

then it came out that Heidi was at the bottom of them, everything

being the result of her excursion of the day before. Fraulein

Rottenmeier sat pale with indignation and did not know at first

how to express her anger. Then she made a sign to Tinette and

Sebastian to withdraw, and turning to Heidi, who was standing by

Clara's couch, quite unable to understand of what sin she had

been guilty, began in a severe voice,--

"Adelaide, I know of only one punishment which will perhaps make

you alive to your ill conduct, for you are an utter little

barbarian, but we will see if we cannot tame you so that you

shall not be guilty of such deeds again, by putting you in a dark

cellar with the rats and black beetles."

Heidi listened in silence and surprise to her sentence, for she

had never seen a cellar such as was now described; the place

known at her grandfather's as the cellar, where the fresh made

cheeses and the new milk were kept, was a pleasant and inviting

place; neither did she know at all what rats and black beetles

were like.

But now Clara interrupted in great distress. "No, no, Fraulein

Rottenmeier, you must wait till papa comes; he has written to say

that he will soon be home, and then I will tell him everything,

and he will say what is to be done with Heidi."

Fraulein Rottenmeier could not do anything against this superior

authority, especially as the father was really expected very

shortly. She rose and said with some displeasure, "As you will,

Clara, but I too shall have something to say to Herr Sesemann."

And with that she left the room.

Two days now went by without further disturbance. Fraulein

Rottenmeier, however, could not recover her equanimity; she was

perpetually reminded by Heidi's presence of the deception that

had been played upon her, and it seemed to her that ever since

the child had come into the house everything had been

topsy-turvy, and she could not bring things into proper order

again. Clara had grown much more cheerful; she no longer found

time hang heavy during the lesson hours, for Heidi was

continually making a diversion of some kind or other. She jumbled

all her letters up together and seemed quite unable to learn

them, and when the tutor tried to draw her attention to their

different shapes, and to help her by showing her that this was

like a little horn, or that like a bird's bill, she would

suddenly exclaim in a joyful voice, "That is a goat!" "That is a

bird of prey!" For the tutor's descriptions suggested all kinds

of pictures to her mind, but left her still incapable of the

alphabet. In the later afternoons Heidi always sat with Clara,

and then she would give the latter many and long descriptions of

the mountain and of her life upon it, and the burning longing to

return would become so overpowering that she always finished with

the words, "Now I must go home! to-morrow I must really go!" But

Clara would try to quiet her, and tell Heidi that she must wait

till her father returned, and then they would see what was to be

done. And if Heidi gave in each time and seemed quickly to regain

her good spirits, it was because of a secret delight she had in

the thought that every day added two more white rolls to the

number she was collecting for grandmother; for she always

pocketed the roll placed beside her plate at dinner and supper,

feeling that she could not bear to eat them, knowing that

grandmother had no white bread and could hardly eat the black

bread which was so hard. After dinner Heidi had to sit alone in

her room for a couple of hours, for she understood now that she

might not run about outside at Frankfurt as she did on the

mountain, and so she did not attempt it. Any conversation with

Sebastian in the dining-room was also forbidden her, and as to

Tinette, she kept out of her way, and never thought of speaking

to her, for Heidi was quite aware that the maid looked scornfully

at her and always spoke to her in a mocking voice. So Heidi had

plenty of time from day to day to sit and picture how everything

at home was now turning green, and how the yellow flowers were

shining in the sun, and how all around lay bright in the warm

sunshine, the snow and the rocks, and the whole wide valley, and

Heidi at times could hardly contain herself for the longing to be

back home again. And Dete had told her that she could go home

whenever she liked. So it came about one day that Heidi felt she

could not bear it any longer, and in haste she tied all the rolls

up in her red shawl, put on her straw hat, and went downstairs.

But just as she reached the hall-door she met Fraulein

Rottenmeier herself, just returning from a walk, which put a stop

to Heidi's journey.

So Heidi had plenty of time from day to day to sit and picture how

everything at home was now turning green, and how the yellow

flowers were shining in the sun

Fraulein Rottenmeier stood still a moment, looking at her from

top to toe in blank astonishment, her eye resting particularly on

the red bundle. Then she broke out,--

"What have you dressed yourself like that for? What do you mean

by this? Have I not strictly forbidden you to go running about in

the streets? And here you are ready to start off again, and going

out looking like a beggar."

"I was not going to run about, I was going home," said Heidi,

frightened.

"What are you talking about! Going home! You want to go home?"

exclaimed Fraulein Rottenmeier, her anger rising. "To run away

like that! What would Herr Sesemann say if he knew! Take care

that he never hears of this! And what is the matter with his

house, I should like to know! Have you not been better treated

than you deserved? Have you wanted for a thing? Have you ever in

your life before had such a house to live in, such a table, or so

many to wait upon you? Have you?

"No," replied Heidi.

"I should think not indeed!" continued the exasperated lady. "You

have everything you can possibly want here, and you are an

ungrateful little thing; it's because you are too well off and

comfortable that you have nothing to do but think what naughty

thing you can do next!"

Then Heidi's feelings got the better of her, and she poured forth

her trouble. "Indeed I only want to go home, for if I stay so

long away Snowflake will begin crying again, and grandmother is

waiting for me, and Greenfinch will get beaten, because I am not

there to give Peter any cheese, and I can never see how the sun

says good-night to the mountains; and if the great bird were to

fly over Frankfurt he would croak louder than ever about people

huddling all together and teaching each other bad things, and not

going to live up on the rocks, where it is so much better."

"Heaven have mercy on us, the child is out of her mind!" cried

Fraulein Rottenmeier, and she turned in terror and went quickly

up the steps, running violently against Sebastian in her hurry.

"Go and bring that unhappy little creature in at once," she

ordered him, putting her hand to her forehead which she had

bumped against his.

Sebastian did as he was told, rubbing his own head as he went,

for he had received a still harder blow.

Heidi had not moved, she stood with her eyes aflame and trembling

all over with inward agitation.

"What, got into trouble again?" said Sebastian in a cheerful

voice; but when he looked more closely at Heidi and saw that she

did not move, he put his hand kindly on her shoulder, and said,

trying to comfort her, "There, there, don't take it to heart so

much; keep up your spirits, that is the great thing! She has

nearly made a hole in my head, but don't you let her bully you."

Then seeing that Heidi still did not stir, "We must go; she

ordered me to take you in."

Heidi now began mounting the stairs, but with a slow, crawling

step, very unlike her usual manner. Sebastian felt quite sad as

he watched her, and as he followed her up he kept trying to

encourage her. "Don't you give in! don't let her make you

unhappy! You keep up your courage! Why we've got such a sensible

little miss that she has never cried once since she was here;

many at that age cry a good dozen times a day. The kittens are

enjoying themselves very much up in their home; they jump about

all over the place and behave as if they were little mad things.

Later we will go up and see them, when Fraulein is out of the

way, shall we?"

Heidi gave a little nod of assent, but in such a joyless manner

that it went to Sebastian's heart, and he followed her with

sympathetic eyes as she crept away to her room.

At supper that evening Fraulein Rottenmeier did not speak, but

she cast watchful looks towards Heidi as if expecting her at any

minute to break out in some extraordinary way; but Heidi sat

without moving or eating; all that she did was to hastily hide

her roll in her pocket.

When the tutor arrived next morning, Fraulein Rottenmeier drew

him privately aside, and confided her fear to him that the change

of air and the new mode of life and unaccustomed surroundings had

turned Heidi's head; then she told him of the incident of the day

before, and of Heidi's strange speech. But the tutor assured her

she need not be in alarm; he had already become aware that the

child was somewhat eccentric, but otherwise quite right in her

mind, and he was sure that, with careful treatment and education,

the right balance would be restored, and it was this he was

striving after. He was the more convinced of this by what he now

heard, and by the fact that he had so far failed to teach her the

alphabet, Heidi seeming unable to understand the letters.

Fraulein Rottenmeier was considerably relieved by his words, and

released the tutor to his work. In the course of the afternoon

the remembrance of Heidi's appearance the day before, as she was

starting out on her travels, suddenly returned to the lady, and

she made up her mind that she would supplement the child's

clothing with various garments from Clara's wardrobe, so as to

give her a decent appearance when Herr Sesemann returned. She

confided her intention to Clara, who was quite willing to make

over any number of dresses and hats to Heidi; so the lady went

upstairs to overhaul the child's belongings and see what was to

be kept and what thrown away. She returned, however, in the

course of a few minutes with an expression of horror upon her

face.

"What is this, Adelaide, that I find in your wardrobe!" she

exclaimed. "I never heard of any one doing such a thing before!

In a cupboard meant for clothes, Adelaide, what do I see at the

bottom but a heap of rolls! Will you believe it, Clara, bread in

a wardrobe! a whole pile of bread! Tinette," she called to that

young woman, who was in the dining-room," go upstairs and take

away all those rolls out of Adelaide's cupboard and the old straw

hat on the table."

"No! no!" screamed Heidi. "I must keep the hat, and the rolls are

for grandmother," and she was rushing to stop Tinette when

Fraulein Rottenmeier took hold of her. "You will stop here, and

all that bread and rubbish shall be taken to the place they

belong to," she said in a determined tone as she kept her hand on

the child to prevent her running forward.

Then Heidi in despair flung herself down on Clara's couch and

broke into a wild fit of weeping, her crying becoming louder and

more full of distress, every minute, while she kept on sobbing

out at intervals, "Now grandmother's' bread is all gone! They

were all for grandmother, and now they are taken away, and

grandmother won't have one," and she wept as if her heart would

break. Fraulein Rottenmeier ran out of the room. Clara was

distressed and alarmed at the child's crying. "Heidi, Heidi," she

said imploringly, "pray do not cry so! listen to me; don't be so

unhappy; look now, I promise you that you shall have just as many

rolls, or more, all fresh and new to take to grandmother when you

go home; yours would have been hard and stale by then. Come,

Heidi, do not cry any more!"

Heidi could not get over her sobs for a long time; she would

never have been able to leave off crying at all if it had not

been for Clara's promise, which comforted her. But to make sure

that she could depend upon it she kept on saying to Clara, her

voice broken with her gradually subsiding sobs, "Will you give me

as many, quite as many, as I had, for grandmother?" And Clara

assured her each time that she would give her as many, "or more,"

she added, "only be happy again."

Heidi appeared at supper with her eyes red with weeping, and when

she saw her roll she could not suppress a sob. But she made an

effort to control herself, for she knew she must sit quietly at

table. Whenever Sebastian could catch her eye this evening he

made all sorts of strange signs, pointing to his own head and

then to hers, and giving little nods as much as to say, "Don't

you be unhappy! I have got it all safe for you."

When Heidi was going to get into bed that night she found her old

straw hat lying under the counterpane. She snatched it up with

delight, made it more out of shape still in her joy, and then,

after wrapping a handkerchief round it, she stuck it in a corner

of the cupboard as far back as she could.

It was Sebastian who had hidden it there for her; he had been in

the dining-room when Tinette was called, and had heard all that

went on with the child and the latter's loud weeping. So he

followed Tinette, and when she came out of Heidi's room carrying

the rolls and the hat, he caught up the hat and said, "I will see

to this old thing." He was genuinely glad to have been able to

save it for Heidi, and that was the meaning of his encouraging

signs to her at supper.

CHAPTER IX

HERR SESEMANN HEARS OF THINGS WHICH ARE NEW TO HIM

A few days after these events there was great commotion and much

running up and down stairs in Herr Sesemann's house. The master

had just returned, and Sebastian and Tinette were busy carrying

up one package after another from the carriage, for Herr Sesemann

always brought back a lot of pretty things for his home. He

himself had not waited to do anything before going in to see his

daughter. Heidi was sitting beside her, for it was late

afternoon, when the two were always together. Father and daughter

greeted each other with warm affection, for they were deeply

attached to one another. Then he held out his hand to Heidi, who

had stolen away into the corner, and said kindly to her, "And

this is our little Swiss girl; come and shake hands with me!

That's right! Now, tell me, are Clara and you good friends with

one another, or do you get angry and quarrel, and then cry and

make it up, and then start quarreling again on the next

occasion?"

"No, Clara is always kind to me," answered Heidi.

"And Heidi," put in Clara quickly, "has not once tried to

quarrel."

"That's all right, I am glad to hear it," said her father, as he

rose from his chair. "But you must excuse me, Clara, for I want

my dinner; I have had nothing to eat all day. Afterwards I will

show you all the things I have brought home with me."

He found Fraulein Rottenmeier in the dining-room superintending

the preparation for his meal, and when he had taken his place she

sat down opposite to him, looking the every embodiment of bad

news, so that he turned to her and said, "What am I to expect,

Fraulein Rottenmeier? You greet me with an expression of

countenance that quite frightens me. What is the matter? Clara

seems cheerful enough."

"Herr Sesemann," began the lady in a solemn voice, "it is a

matter which concerns Clara; we have been frightfully imposed

upon."

"Indeed, in what way?" asked Herr Sesemann as he went on calmly

drinking his wine.

"We had decided, as you remember, to get a companion for Clara,

and as I knew how anxious you were to have only those who were

well-behaved and nicely brought up about her, I thought I would

look for a little Swiss girl, as I hoped to find such a one as I

have often read about, who, born as it were of the mountain air,

lives and moves without touching the earth."

"Still I think even a Swiss child would have to touch the earth

if she wanted to go anywhere," remarked Herr Sesemann, "otherwise

they would have been given wings instead of feet."

"Ah, Herr Sesemann, you know what I mean," continued Fraulein

Rottenmeier. "I mean one so at home among the living creatures of

the high, pure mountain regions, that she would be like some

idealistic being from another world among us."

"And what could Clara do with such an idealistic being as you

describe, Fraulein Rottenmeier."

"I am not joking, Herr Sesemann, the matter is a more serious one

than you think; I have been shockingly, disgracefully imposed

upon."

"But how? what is there shocking and disgraceful? I see nothing

shocking in the child," remarked Herr Sesemann quietly.

"If you only knew of one thing she has done, if you only knew of

the kind of people and animals she has brought into the house

during your absence! The tutor can tell you more about that."

"Animals? what am I to understand by animals, Fraulein

Rottenmeier?"

"It is past understanding; the whole behavior of the child would

be past understanding, if it were not that at times she is

evidently not in her right mind."

Herr Sesemann had attached very little importance to what was

told him up till now--but not in her right mind! that was more

serious and might be prejudicial to his own child. Herr Sesemann

looked very narrowly at the lady opposite to assure himself that

the mental aberration was not on her side. At that moment the

door opened and the tutor was announced.

"Ah! here is some one," exclaimed Herr Sesemann, "who will help

to clear up matters for me. Take a seat," he continued, as he

held out his hand to the tutor. "You will drink a cup of coffee

with me--no ceremony, I pray! And now tell me, what is the matter

with this child that has come to be a companion to my daughter?

What is this strange thing I hear about her bringing animals into

the house, and is she in her right senses?"

The tutor felt he must begin with expressing his pleasure at Herr

Sesemann's return, and with explaining that he had come in on

purpose to give him welcome, but Herr Sesemann begged him to

explain without delay the meaning of all he had heard about

Heidi. The tutor started in his usual style. "If I must give my

opinion about this little girl, I should like first to state

that, if on one side, there is a lack of development which has

been caused by the more or less careless way in which she has

been brought up, or rather, by the neglect of her education, when

young, and by the solitary life she has led on the mountain,

which is not wholly to be condemned; on the contrary, such a life

has undoubtedly some advantages in it, if not allowed to overstep

a certain limit of time--"

"My good friend," interrupted Herr Sesemann, "you are giving

yourself more trouble than you need. I only want to know if the

child has caused you alarm by any animals she has brought into

the house, and what your opinion is altogether as to her being a

fit companion or not for my daughter?"

"I should not like in any way to prejudice you against her,"

began the tutor once more; "for if on the one hand there is a

certain inexperience of the ways of society, owing to the

uncivilised life she led up to the time of her removal to

Frankfurt, on the other hand she is endowed with certain good

qualities, and, taken on the whole--"

"Excuse me, my dear sir, do not disturb yourself, but I must--I

think my daughter will be wanting me," and with that Herr

Sesemann quickly left the room and took care not to return. He

sat himself down beside his daughter in the study, and then

turning to Heidi, who had risen, "Little one, will you fetch me,"

he began, and then paused, for he could not think what to ask

for, but he wanted to get the child out of the room for a little

while, "fetch me fetch me a glass of water."

"Fresh water?" asked Heidi.

"Yes--Yes--as fresh as you can get it," he answered. Heidi

disappeared on the spot.

"And now, my dear little Clara," he said, drawing his chair

nearer and laying her hand in his, "answer my questions clearly

and intelligibly: what kind of animals has your little companion

brought into the house, and why does Fraulein Rottenmeier think

that she is not always in her right mind?"

Clara had no difficulty in answering. The alarmed lady had spoken

to her also about Heidi's wild manner of talking, but Clara had

not been able to put a meaning to it. She told her father

everything about the tortoise and the kittens, and explained to

him what Heidi had said the day Fraulein Rottenmeier had been put

in such a fright. Herr Sesemann laughed heartily at her recital.

"So you do not want me to send the child home again," he asked,

you are not tired of having her here?"

"Oh, no, no," Clara exclaimed, "please do not send her away. Time

has passed much more quickly since Heidi was here, for something

fresh happens every day, and it used to be so dull, and she has

always so much to tell me."

"That's all right then--and here comes your little friend. Have

you brought me some nice fresh water?" he asked as Heidi handed

him a glass.

"Yes, fresh from the pump," answered Heidi.

"You did not go yourself to the pump?" said Clara.

"Yes I did; it is quite fresh. I had to go a long way, for there

were such a lot of people at the first pump; so I went further

down the street, but there were just as many at the second pump,

but I was able to get some water at the one in the next street,

and the gentleman with the white hair asked me to give his kind

regards to Herr Sesemann."

"You have had quite a successful expedition," said Herr Sesemann

laughing, "and who was the gentleman?"

"He was passing, and when he saw me he stood still and said, 'As

you have a glass will you give me a drink; to whom are you taking

the water?' and when I said, 'To Herr Sesemann,' he laughed very

much, and then he gave me that message for you, and also said he

hoped you would enjoy the water."

"Oh, and who was it, I wonder, who sent me such good wishes--tell

me what he was like," said Herr Sesemann.

"He was kind and laughed, and he had a thick gold chain and a

gold thing hanging from it with a large red stone, and a horse's

head at the top of his stick."

"It's the doctor--my old friend the doctor," exclaimed Clara and

her father at the same moment, and Herr Sesemann smiled to

himself at the thought of what his friend's opinion must have

been of this new way of satisfying his thirst for water.

That evening when Herr Sesemann and Fraulein Rottenmeier were

alone, settling the household affairs, he informed her that he

intended to keep Heidi; he found the child in a perfectly right

state of mind, and his daughter liked her as a companion. "I

desire, therefore," he continued, laying stress upon his words,

"that the child shall be in every way kindly treated, and that

her peculiarities shall not be looked upon as crimes. If you find

her too much for you alone, I can hold out a prospect of help,

for I am shortly expecting my mother here on a long visit, and

she, as you know, can get on with anybody, whatever they may be

like."

"O yes, I know," replied Fraulein Rottenmeier, but there was no

tone of relief in her voice as she thought of the coming help.

Herr Sesemann was only home for a short time; he left for Paris

again before the fortnight was over, comforting Clara, who could

not bear that he should go from her again so soon, with the

prospect of her grandmother's arrival, which was to take place in

a few days' time. Herr Sesemann had indeed only just gone when a

letter came from Frau Sesemann, announcing her arrival on the

following day, and stating the hour when she might be expected,

in order that a carriage should be sent to meet her at the

station. Clara was overjoyed, and talked so much about her

grandmother that evening, that Heidi began also to call her

"grandmamma," which brought down on her a look of displeasure

from Fraulein Rottenmeier; this, however, had no particular

effect on Heidi, for she was accustomed now to being continually

in that lady's black books. But as she was going to her room that

night, Fraulein Rottenmeier waylaid her, and drawing her into her

own, gave her strict injunctions as to how she was to address

Frau Sesemann when she arrived; on no account was she to call her

"grandmamma," but always to say "madam" to her. "Do you

understand?" said the lady, as she saw a perplexed expression on

Heidi's face. The latter had not understood, but seeing the

severe expression of the lady's face she did not ask for more

explanation.

CHAPTER X

ANOTHER GRANDMOTHER

There was much expectation and preparation about the house on the

following evening, and it was easy to see that the lady who was

coming was one whose opinion was highly thought of, and for whom

everybody had a great respect. Tinette had a new white cap on her

head, and Sebastian collected all the footstools he could find

and placed them in convenient spots, so that the lady might find

one ready to her feet whenever she chose to sit. Fraulein

Rottenmeier went about surveying everything, very upright and

dignified, as if to show that though a rival power was expected,

her own authority was not going to be extinguished.

And now the carriage came driving up to the door, and Tinette and

Sebastian ran down the steps, followed with a slower and more

stately step by the lady, who advanced to greet the guest. Heidi

had been sent up to her room and ordered to remain there until

called down, as the grandmother would certainly like to see Clara

alone first. Heidi sat herself down in a corner and repeated her

instructions over to herself. She had not to wait long before

Tinette put her head in and said abruptly, "Go downstairs into

the study."

Heidi had not dared to ask Fraulein Rottenmeier again how she was

to address the grandmother: she thought the lady had perhaps made

a mistake, for she had never heard any one called by other than

their right name. As she opened the study door she heard a kind

voice say, "Ah, here comes the child! Come along in and let me

have a good look at you."

Heidi walked up to her and said very distinctly in her clear

voice, "Good-evening," and then wishing to follow her

instructions called her what would be in English "Mrs. Madam."

"Well!" said the grandmother, laughing, "is that how they address

people in your home on the mountain?"

"No," replied Heidi gravely, "I never knew any one with that name

before."

"Nor I either," laughed the grandmother again as she patted

Heidi's cheek. "Never mind! when I am with the children I am

always grandmamma; you won't forget that name, will you?"

"No, no," Heidi assured her, "I often used to say it at home."

"I understand," said the grandmother, with a cheerful little nod

of the head. Then she looked more closely at Heidi, giving

another nod from time to time, and the child looked back at her

with steady, serious eyes, for there was something kind and

warm-hearted about this new-comer that pleased Heidi, and indeed

everything to do with the grandmother attracted her, so that she

could not turn her eyes away. She had such beautiful white hair,

and two long lace ends hung down from the cap on her head and

waved gently about her face every time she moved, as if a soft

breeze were blowing round her, which gave Heidi a peculiar

feeling of pleasure.

"And what is your name, child?" the grandmother now asked.

"I am always called Heidi; but as I am now to be called Adelaide,

I will try and take care--" Heidi stopped short, for she felt a

little guilty; she had not yet grown accustomed to this name; she

continued not to respond when Fraulein Rottenmeier suddenly

addressed her by it, and the lady was at this moment entering the

room.

"Frau Sesemann will no doubt agree with me," she interrupted,

"that it was necessary to choose a name that could be pronounced

easily, if only for the sake of the servants."

"My worthy Rottenmeier," replied Frau Sesemann, "if a person is

called 'Heidi' and has grown accustomed to that name, I call her

by the same, and so let it be."

Fraulein Rottenmeier was always very much annoyed that the old

lady continually addressed her by her surname only; but it was no

use minding, for the grandmother always went her own way, and so

there was no help for it. Moreover the grandmother was a keen old

lady, and had all her five wits about her, and she knew what was

going on in the house as soon as she entered it.

When on the following day Clara lay down as usual on her couch

after dinner, the grandmother sat down beside her for a few

minutes and closed her eyes, then she got up again as lively as

ever, and trotted off into the dining-room. No one was there.

"She is asleep, I suppose," she said to herself, and then going

up to Fraulein Rottenmeier's room she gave a loud knock at the

door. She waited a few minutes and then Fraulein Rottenmeier

opened the door and drew back in surprise at this unexpected

visit.

"Where is the child, and what is she doing all this time? That is

what I came to ask," said Frau Sesemann.

"She is sitting in her room, where she could well employ herself

if she had the least idea of making herself useful; but you have

no idea, Frau Sesemann, of the out-of-the-way things this child

imagines and does, things which I could hardly repeat in good

society."

"I should do the same if I had to sit in there like that child, I

can tell you; I doubt if you would then like to repeat what I

did, in good society! Go and fetch the child and bring her to my

room; I have some pretty books with me that I should like to give

her."

"That is just the misfortune," said Fraulein Rottenmeier with a

despairing gesture, "what use are books to her? She has not been

able to learn her A B C even, all the long time she has been

here; it is quite impossible to get the least idea of it into her

head, and that the tutor himself will tell you; if he had not the

patience of an angel he would have given up teaching her long

ago."

"That is very strange," said Frau Sesemann, "she does not look to

me like a child who would be unable to learn her alphabet.

However, bring her now to me, she can at least amuse herself with

the pictures in the books."

Fraulein Rottenmeier was prepared with some further remarks, but

the grandmother had turned away and gone quickly towards her own

room. She was surprised at what she had been told about Heidi's

incapacity for learning, and determined to find out more

concerning this matter, not by inquiries from the tutor, however,

although she esteemed him highly for his uprightness of

character; she had always a friendly greeting for him, but always

avoided being drawn into conversation with him, for she found his

style of talk somewhat wearisome.

Heidi now appeared and gazed with open-eyed delight and wonder at

the beautiful colored pictures in the books which the grandmother

gave her to look at. All of a sudden, as the latter turned over

one of the pages to a fresh picture, the child gave a cry. For a

moment or two she looked at it with brightening eyes, then the

tears began to fall, and at last she burst into sobs. The

grandmother looked at the picture--it represented a green

pasture, full of young animals, some grazing and others nibbling

at the shrubs. In the middle was a shepherd leaning upon his

staff and looking on at his happy flock. The whole scene was

bathed in golden light, for the sun was just sinking below the

horizon.

The grandmother laid her hand kindly On Heidi's.

"Don't cry, dear child, don't cry," she said, "the picture has

reminded you perhaps of something. But see, there is a beautiful

tale to the picture which I will tell you this evening. And there

are other nice tales of all kinds to read and to tell again. But

now we must have a little talk together, so dry your tears and

come and stand in front of me, so that I may see you well--there,

now we are happy again."

But it was some little time before Heidi could overcome her sobs.

The grandmother gave her time to recover herself, saying cheering

words to her now and then, "There, it's all right now, and we are

quite happy again."

When at last she saw that Heidi was growing calmer, she said,

"Now I want you to tell me something. How are you getting on in

your school-time; do you like your lessons, and have you learnt a

great deal?"

"O no!" replied Heidi, sighing, "but I knew beforehand that it

was not possible to learn."

"What is it you think impossible to learn?"

"Why, to read, it is too difficult."

"You don't say so! and who told you that?"

"Peter told me, and he knew all about it, for he had tried and

tried and could not learn it."

"Peter must be a very odd boy then! But listen, Heidi, we must

not always go by what Peter says, we must try for ourselves. I am

certain that you did not give all your attention to the tutor

when he was trying to teach you your letters."

"It's of no use," said Heidi in the tone of one who was ready to

endure what could not be cured.

"Listen to what I have to say," continued the grandmother. "You

have not been able to learn your alphabet because you believed

what Peter said; but now you must believe what I tell you--and I

tell you that you can learn to read in a very little while, as

many other children do, who are made like you and not like Peter.

And now hear what comes after--you see that picture with the

shepherd and the animals--well, as soon as you are able to read

you shall have that book for your own, and then you will know all

about the sheep and the goats, and what the shepherd did, and the

wonderful things that happened to him, just as if some one were

telling you the whole tale. You will like to hear about all that,

won't you?"

Heidi had listened with eager attention to the grandmother's

words and now with a sigh exclaimed, "Oh, if only I could read

now!"

"It won't take you long now to learn, that I can see; and now we

must go down to Clara; bring the books with you." And hand in

hand the two returned to the study."

Since the day when Heidi had so longed to go home, and Fraulein

Rottenmeier had met her and scolded her on the steps, and told

her how wicked and ungrateful she was to try and run away, and

what a good thing it was that Herr Sesemann knew nothing about

it, a change had come over the child. She had at last understood

that day that she could not go home when she wished as Dete had

told her, but that she would have to stay on in Frankfurt for a

long, long time, perhaps for ever. She had also understood that

Herr Sesemann would think it ungrateful of her if she wished to

leave, and she believed that the grandmother and Clara would

think the same. So there was nobody to whom she dared confide her

longing to go home, for she would not for the world have given

the grandmother, who was so kind to her, any reason for being as

angry with her as Fraulein Rottenmeier had been. But the weight

of trouble on the little heart grew heavier and heavier; she

could no longer eat her food, and every day she grew a little

paler. She lay awake for long hours at night, for as soon as she

was alone and everything was still around her, the picture of the

mountain with its sunshine and flowers rose vividly before her

eyes; and when at last she fell asleep it was to dream of the

rocks and the snow-field turning crimson in the evening light,

and waking in the morning she would think herself back at the hut

and prepare to run joyfully out into--the sun--and then--there

was her large bed, and here she was in Frankfurt far, far away

from home. And Heidi would often lay her face down on the pillow

and weep long and quietly so that no one might hear her.

Heidi's unhappiness did not escape the grandmother's notice. She

let some days go by to see if the child grew brighter and lost

her down-cast appearance. But as matters did not mend, and she

saw that many mornings Heidi had evidently been crying before she

came downstairs, she took her again into her room one day, and

drawing the child to her said, "Now tell me, Heidi, what is the

matter; are you in trouble?"

But Heidi, afraid if she told the truth that the grandmother

would think her ungrateful, and would then leave off being so

kind to her, answered, can't tell you."

"Well, could you tell Clara about it?"

"Oh, no, I cannot tell any one," said Heidi in so positive a

tone, and with a look of such trouble on her face, that the

grandmother felt full of pity for the child.

"Then, dear child, let me tell you what to do: you know that when

we are in great trouble, and cannot speak about it to anybody, we

must turn to God and pray Him to help, for He can deliver us from

every care, that oppresses us. You understand that, do you not?

You say your prayers every evening to the dear God in Heaven, and

thank Him for all He has done for you, and pray Him to keep you

from all evil, do you not?"

"No, I never say any prayers," answered Heidi.

"Have you never been taught to pray, Heidi; do you not know even

what it means?"

"I used to say prayers with the first grandmother, but that is a

long time ago, and I have forgotten them."

"That is the reason, Heidi, that you are so unhappy, because you

know no one who can help you. Think what a comfort it is when the

heart is heavy with grief to be able at any moment to go and tell

everything to God, and pray Him for the help that no one else can

give us. And He can help us and give us everything that will make

us happy again."

A sudden gleam of joy came into Heidi's eyes. "May I tell Him

everything, everything?"

"Yes, everything, Heidi, everything."

Heidi drew her hand away, which the grandmother was holding

affectionately between her own, and said quickly, "May I go?"

"Yes, of course," was the answer, and Heidi ran out of the room

into her own, and sitting herself on a stool, folded her hands

together and told God about everything that was making her so sad

and unhappy, and begged Him earnestly to help her and to let her

go home to her grandfather.

It was about a week after this that the tutor asked Frau

Sesemann's permission for an interview with her, as he wished to

inform her of a remarkable thing that had come to pass. So she

invited him to her room, and as he entered she held out her hand

in greeting, and pushing a chair towards him, "I am pleased to

see you," she said, "pray sit down and tell me what brings you

here; nothing bad, no complaints, I hope?"

"Quite the reverse," began the tutor. "Something has happened

that I had given up hoping for, and which no one, knowing what

has gone before, could have guessed, for, according to all

expectations, that which has taken place could only be looked

upon as a miracle, and yet it really has come to pass and in the

most extraordinary manner, quite contrary to all that one could

anticipate--"

"Has the child Heidi really learnt to read at last?" put in Frau

Sesemann.

The tutor looked at the lady in speechless astonishment. At last

he spoke again. "It is indeed truly marvellous, not only because

she never seemed able to learn her A B C even after all my full

explanations, and after spending unusual pains upon her, but

because now she has learnt it so rapidly, just after I had made

up my mind to make no further attempts at the impossible but to

put the letters as they were before her without any dissertation