Prudentia: Are Your Favorite Online Services Playing Fair?

Picture this. It’s a warm summer evening. After a long day, your roommate and you settle down on the couch to indulge your respective Internet-fueled pastimes. You’ve pulled up undeniably adorable cat videos on YouTube, and your roommate is catching up on the latest episode of her favorite TV show on another streaming service. But, alas! Your cat videos keep buffering, and when they do finally play, you are forced to bear witness to grainy, low quality video, the likes of which you would have expected only a decade ago. You glance over to your roommate to commiserate, but—egad, gadzooks—her show is playing at a flawless 4K, with no stuttering in sight! As Prudentia, our Internet Fairness Watchdog, will reveal to you shortly, this isn’t just bad luck: the design choices made by various Internet services can lead to deeply unfair outcomes when they compete for limited bandwidth.

Past work has typically pointed the finger at Congestion Control Algorithms (CCAs), a network-stack component which determines how quickly an application sends data, as the likely cause of unfair outcomes. And indeed, CCAs have been shown to be unfair to each other, and sometimes, even themselves. For example, past work has shown that Google’s CCA, BBR, was fundamentally unfair to the erstwhile incumbent CCA, Cubic, in certain network conditions. Cubic, in turn, was unfair to its predecessor , NewReno. Recent work has shown that BBR is unfair to even other BBR instances at high flow counts . However, these analyses neglect the fact that modern Internet services, such as video streaming and conferencing applications, perform application-level optimizations on top of CCAs to improve the user experience, which could impact fairness outcomes. For example, Video streaming services, like YouTube, Vimeo and Netflix, use Adaptive-Bitrate (ABR) algorithms to select a stable video quality for viewers. Real time video-conferencing services, like Zoom and Google Meet must additionally ensure they do not flood the network, which would cause delays and jitter for users. In spite of this, fairness research continues to focus on CCAs, with almost no service-level evaluations. This motivated us to build Prudentia, the Internet Fairness Watchdog, to bridge this gap, and answer a simple but critical question: Are there ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ when popular services compete for bandwidth on the Internet today, and are there mechanisms beyond the CCA that determine these outcomes?

The Heart of a Watchdog

Typical Internet testbeds run in emulated or simulated environments, where both the services generating traffic and the clients consuming them exist within the testbed network. This allows complete visibility and control into the network path between the clients and the services. However, applying this approach to real Internet services would require replicating the service in a local testbed, which given their often proprietary nature is error-prone and likely impossible. Alas, is all lost? Will Internet service fairness remain a mystery, divined occasionally by blood sacrifices to questionable mystics?

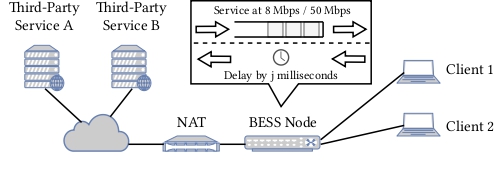

Not at all! Prudentia retains fidelity by using actual Google Chrome instances (fully automated with Selenium . Don’t worry, no interns were imprisoned in our server rooms.) running on commodity hardware (2023 M2 Mac Minis ). We use these to access real Internet services using their official browser based clients, exactly like a real user. And to retain control over the bottleneck link, the most important component of the network path when it comes to fairness, we route all traffic to and from the clients through BESS , a software switch from Berkeley, set to emulate a lower bandwidth than typical upstream links. This lets us enjoy the best of both worlds: realism by accessing deployed services just as a user would, and the configurability of emulated networks by controlling the bottleneck link.

We configure BESS to emulate two distinct link speeds: a highly-constrained setting, with a bandwidth of 8 Mbps, and a moderately-constrained setting, with a bandwidth of 50 Mbps, which correspond to the 10th and 50th-percentile of residential bandwidths on Ookla’s SpeedTest as of 2023. BESS also sets the bottleneck queue size, and normalizes the base network path delay (typically referred to as RTT ) for more reliable measurements across services. Prudentia calculates the fraction of bandwidth that each service obtains relative to its “fair share”, which we define as half the available bandwidth or the maximum bandwidth a service can use, whichever is lesser (this accounts for services like Netflix, which at its highest quality still consumes just 8 Mbps, less than half the bandwidth available in the moderately-constrained setting).

We use this unique infrastructure to test a diverse range of services spanning streaming video on demand, file distribution, web browsing, real-time video conferencing, and the baseline CCAs NewReno, Cubic and BBR using iPerf3 , a pair at a time. The results from Prudentia’s tests are available to all at https://internetfairness.net/ —providing the public access to an independent watchdog that quantifies which services win and lose and by how much. We hope this enables both service owners and the wider community identify and correct excessively unfair outcomes.

Internet Fairness Outcomes

Prudentia has been running continuously for over two years, and has uncovered a wealth of insights into service interactions during that time. While all the findings (and more details about the methodology) are discussed in the research paper , we highlight a few of them here:

Unequal Outcomes Are Common

First and foremost, Prudentia finds that unfair bandwidth allocations are not rare, and are in fact a common occurrence when services compete for bandwidth. While the possibility of CCA-level unfairness was well known from past fairness research, the extent to which it occurs on the Internet with actual services was unclear before Prudentia’s measurements.

The CCA Alone Doesn’t Tell the Whole Story

Prudentia was birthed by the hypothesis that testing CCAs alone is not sufficient to predict the unfairness exhibited by real Internet services. This is vindicated by its finding that services using variants of the same CCA can exhibit vastly different fairness behaviors—best exemplified by YouTube, and the popular file-hosting service Mega . Both these services use variants of the CCA BBR. However, Mega was found to be one of the most contentious services, while YouTube was one of the least contentious, with competing services obtaining 50% and 120% of their fair bandwidth shares respectively. Mega’s contentiousness is likely due to its use of multiple flows, while YouTube’s sensitivity (allowing competing services a larger share of the available bandwidth) is probably linked to its ABR algorithm prioritizing stability, and the discrete bitrate levels that videos are encoded for. These are both findings that would have been impossible to arrive at by testing just the CCA, demonstrating that testing the entire application stack is necessary to capture real-world fairness outcomes.

Multiple Multi-Flow Services Exist, with Varying Fairness Impacts

CCAs are designed to be flow-level fair, with each connection getting an equal share of bandwidth. It is therefore well-known in the Internet fairness community that if a service opens multiple connections, it is likely to obtain more than its fair share of bandwidth. What is surprising however, is that in spite of this knowledge, multiple services that Prudentia tested use more than 1 concurrent connection to serve traffic, resulting in varying extents of unfairness. Mega uses a custom javascript framework to open up to 5 concurrent BBR flows to download files, while Netflix and Vimeo use up to 4 NewReno and 2 BBR flows concurrently, respectively. As seen in the fairness heatmap above, this results in Mega having the most unfair outcomes, followed by Netflix in bandwidth constrained settings. Vimeo on the other hand, surprisingly provides typically fair outcomes, likely due to its ABR algorithm.

Fairness Outcomes are Often Anomalous

A surprising finding is that many unfair outcomes are anomalous, due to specific interactions between certain services, and don’t always follow a transitive pattern. For example, one might assume that if a service α is unfair to service β, and β is unfair to service γ, α will also be unfair to γ. However, this is not always the case. For example, consider the following sets of fairness outcomes:

| α | β | γ | BW (Mbps) | Fair Share Obtained | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| by β (vs α) | by γ (vs β) | by γ (vs α) | ||||

| Mega | NewReno | Vimeo | 50 | 22% | 58% | 104% |

| Cubic | Dropbox | NewReno | 8 | 99% | 106% | 60% |

| BBR | OneDrive | YouTube | 50 | 108% | 106% | 58% |

As seen in the first row, NewReno obtains just 22% of its fair share when competing against Mega, and Vimeo obtains just 58% of its fair share when competing against NewReno. Since Mega is unfair to NewReno, and NewReno is unfair to Vimeo, one might expect Mega to be unfair to Vimeo too. However, when competing against Mega, Vimeo gets more than its fair share of bandwidth!

This suggests that there are unlikely to be “bellwether” services whose interaction can predict a service’s general fairness properties. Reliable fairness outcome monitoring would therefore require continuous pairwise testing of popular services.

In a Nutshell

Prudentia’s results show that unfair outcomes are common on the Internet, and that testing the CCA alone is not always sufficient to predict these outcomes. This impresses upon us both the need for an independent fairness watchdog like Prudentia, and the necessity of testing services in addition to CCAs. Some of Prudentia’s findings confirmed long-standing knowledge but showed these behaviors are still deployed in popular services today, such as the negative outcomes from using multiple flows or buffer-filling CCAs (the buffer-filling CCAs tested are NewReno, used by Netflix, and Cubic, the most commonly deployed CCA , and used by OneDrive). Other findings were novel, like the discovery and characterization of multi-flow services such as Mega, and the unexpected interactions between certain services. Many results were surprising and hard to diagnose without access to the proprietary application-level algorithms powering many of these services, emphasizing the need to include service owners in the conversation. Together, guided by Prudentia, we believe that we can move towards a fairer, more performant Internet for everyone.

What’s Next for Prudentia?

Future work for Prudentia includes scaling up to test more services, a wider range of network settings (like different bottleneck queue sizes, RTTs, random packet loss), and various vantage points globally. This expanded testing will provide an even richer understanding of how services interact in the diverse environments seen on the Internet. Prudentia continues to serve as an essential independent watchdog, shedding light on the critical issue of Internet fairness at the application level. By evaluating full application stacks under contention, it provides valuable data that encourages service providers and researchers to consider the broader impact of their design choices on the miraculous shared network that is the Internet. Want to see the results or submit a service for testing? Visit the Prudentia website at https://www.internetfairness.net!