Logical and Classical Planning Agents

Logical Pacman,

Food is good AND ghosts are bad,

Spock would be so proud.

Introduction

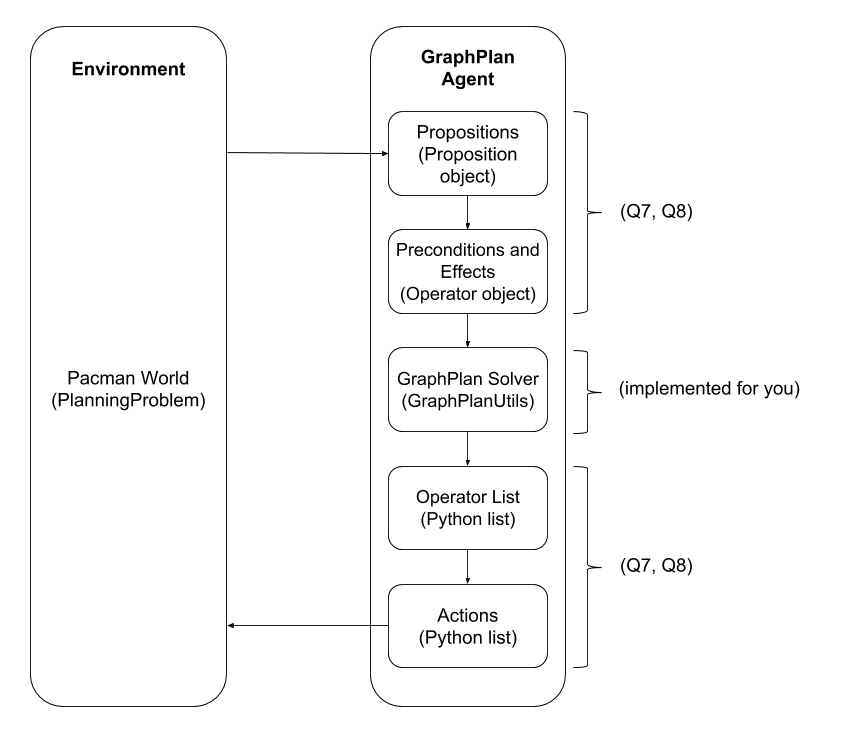

In this project, you will implement two different planning frameworks. In the first, your Pacman agent will logically plan his way to the goal. You will write software that generates the logical sentences describing moving around the board and eating food. You will encode initial states and goals and use logical inference to find action sequences that are consistent with these. In the second framework, your Pacman agent will use GraphPlan to find its way to the goal. You will again encode initial and goal states, and you will write the action operators that GraphPlan will use to move and eat its way towards its goal.

These diagrams outline the different steps of the propositional logic and classical planning processes. Notice that the process is the same but the representation of states and actions are different.

As in previous programming assignments, this assignment includes an autograder for you to grade your answers on your machine. This can be run with the command:

python3.13 autograder.py

See the autograder tutorial in Project 0 for more information about using the autograder.

The code for this project consists of several Python files, some of which you will need to read and understand in order to complete the assignment, and some of which you can ignore. You can download all the code and supporting files here: logic_plan.zip.

Files you will edit

logicPlan.py |

Where all of your logic planning algorithms will reside. |

analysis.py |

A file to put your answers to questions given in the project. |

graphPlan.py |

Where all of your GraphPlan classical planning algorithms will reside. |

Files you might want to look at

logic.py |

Propsitional logic code originally from https://code.google.com/p/aima-python/ with modifications for our project. There are several useful utility functions for working with logic in here. |

logicAgents.py |

The file that defines in logical planning form the two specific problems that Pacman will encounter in this project. |

graphPlanAgents.py |

The file that defines in graph planning form the two specific problems that Pacman will encounter in this project. |

rocket.py |

An example GraphPlan problem formulation. |

graphplanUtils.py |

Utility classes and functions used for GraphPlan planning, like instances, variables, and operators. |

pycosat_test.py |

Quick test main function that checks that the pycosat module is installed correctly. |

game.py |

The logic behind how the Pacman world works. The only thing you might want to look at in here is the Grid class. |

test_cases/ |

Directory containing the test cases for each question |

Files you will not edit

pacman.py |

The main file that runs Pacman games. |

logic_util.py |

Utility functions for logic.py |

util.py |

Utility functions primarily for other projects. |

logic_planTestClasses.py |

Project specific autograding test classes |

graphicsDisplay.py |

Graphics for Pacman |

graphicsUtils.py |

Support for Pacman graphics |

textDisplay.py |

ASCII graphics for Pacman |

ghostAgents.py |

Agents to control ghosts |

keyboardAgents.py |

Keyboard interfaces to control Pacman |

layout.py |

Code for reading layout files and storing their contents |

autograder.py |

Project autograder |

testParser.py |

Parses autograder test and solution files |

testClasses.py |

General autograding test classes |

Files to Edit and Submit: You will fill in portions of logicPlan.py,

analysis.py, and graphPlan.py during the assignment. You should submit these files

with your code and comments. Please do not change the other files in this distribution or submit

any of our original files other than these files.

Evaluation: Your code will be autograded for technical correctness. Please do not change the names of any provided functions or classes within the code, or you will wreak havoc on the autograder. However, the correctness of your implementation -- not the autograder's judgements -- will be the final judge of your score. If necessary, we will review and grade assignments individually to ensure that you receive due credit for your work.

Academic Dishonesty: We will be checking your code against other submissions in the class for logical redundancy. If you copy someone else's code and submit it with minor changes, we will know. These cheat detectors are quite hard to fool, so please don't try. We trust you all to submit your own work only; please don't let us down. If you do, we will pursue the strongest consequences available to us.

Getting Help: You are not alone! If you find yourself stuck on something, contact the course staff for help. Office hours, section, and the discussion forum are there for your support; please use them. If you can't make our office hours, let us know and we will schedule more. We want these projects to be rewarding and instructional, not frustrating and demoralizing. But, we don't know when or how to help unless you ask.

Discussion: Please be careful not to post spoilers.

Assignment FAQ

We have compiled a list of frequently asked questions and common mistakes on various problems in this assignment. Please read this list carefully, and refer back to this before asking any questions on Piazza.

- Question 1: Read

PropSymbolExprclass carefully and make sure you know how to construct fluents - Question 3: You may assume the time steps are continuous and each time step corresponds to an unique action

- Question 5: Check the

Gridclass ingame.pyfor the wall class - Question 6:

wallis of the same class aswall_gridin Q5- Positions are 1-indexed

- Pay close attention to how we use propositions and variables/instances to represent our problem

- If it timeouts make sure

atMostOne/exactlyOneboth return CNF form (revisit Q2) - If all helper functions return CNF and it still times out, check and remove redundant logic expressions

- Make use of

GenerateAllTransitionsfrom Q5

- Question 8: For the first question, give your answer as an non-negative integer

- Question 9: Read

rocket.pyif you don’t know where to start

The Expr Class

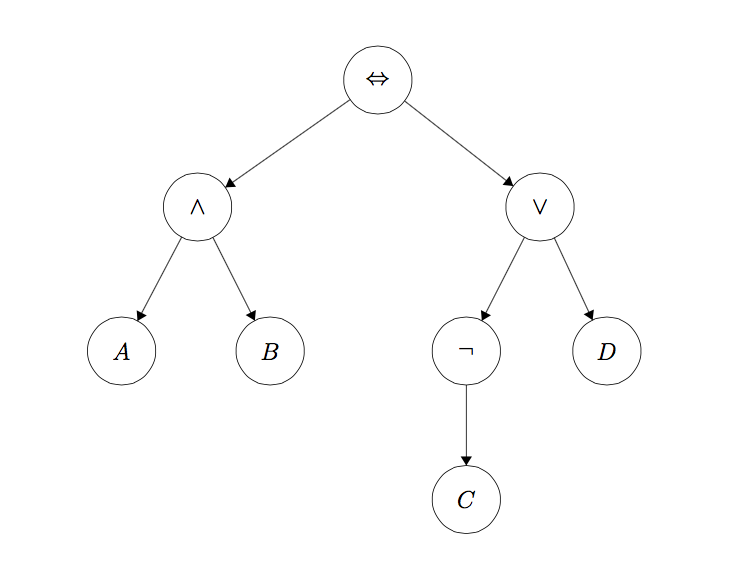

In the first part of this project, you will be working with the Expr class defined in

logic.py to build propositional logic sentences. An Expr object is implemented as

a tree with logical operators (\(\land, \lor, \neg, \Rightarrow, \Leftrightarrow\)) at each node and with

literals (\(A, B, C\)) at the leaves. The sentence

\[ (A \land B) \Leftrightarrow (\neg C \lor D) \]

would be represented as the tree

To instantiate a symbol named 'A', call the constructor like this:

A = Expr('A')

The Expr class allows you to use Python operators to build up these expressions. The following

are the available Python operators and their meanings:

~A: \(\neg A\)A & B: \(A \land B\)A | B: \(A \lor B\)A >> B: \(A \Rightarrow B\)A % B: \(A \Leftrightarrow B\)

So to build the expression \(A \land B\), you would type this:

A = Expr('A')

B = Expr('B')

a_and_b = A & B

Note: A to the left of the assignment operator in that example is just a Python

variable name, i.e. symbol1 = Expr('A') would have worked just as well.)

Important: A & B & C will give the expression

((A & B) & C). If instead you want (A & B & C), as you will for

these problems, use logic.conjoin, which takes a list of expressions as input and returns one

expression that is the conjunction of all the inputs. The & operator in Python is a binary

operator and builds an unbalanced binary tree if you chain it several times, whereas conjoin

builds a tree that is one level deep with all the inputs extending directly from the &

operator at the root. logic.disjoin is similarly defined for |. The autograder for

Question 1 will require that you use logic.conjoin and logic.disjoin wherever you

could otherwise chain several & operators or several | operators. If you keep

with this convention for later problems, it will help with debugging because you will get more readable

expressions.

There is additional, more detailed documentation for the Expr class in logic.py.

Tips

- When creating a symbol with

Expr, it must start with an upper case character. You will get non-obvious errors later if you don't follow this convention. - Be careful creating and combining

Exprinstances. For example, if you intend to create the expressionx = Expr('A') & Expr('B'), you don't want to accidentally typex = Expr('A & B'). The former will be a logical expression of the symbol 'A' and the symbol 'B', while the latter will be a single symbol (Expr) named 'A & B'.

SAT Solver Setup

A SAT (satisfiability) solver takes a logic expression which encodes the rules of the world and returns a model (true and false assignments to logic symbols) that satisfies that expression if such a model exists. To efficiently find a possible model from an expression, we take advantage of the pycosat module, which is a Python wrapper around the picoSAT library.

Unfortunately, this requires installing this module/library on each machine.

To install this software in the Andrew Linux servers:

ssh -Y <andrewid>@unix.andrew.cmu.edu- Install pycosat:

python3.13 -m pip install --user pycosat --upgrade setuptoolsThere should be no errors.

To install this software on your own machine (Mac and Unix), please follow these steps:

- Install pycosat:

python3.13 -m pip install pycosat - If the line above does not work try upgrading the set up tools by

python3.13 -m pip install --user pycosat --upgrade setuptools

To install this software on your own machine (Windows), please follow these steps:

- Install pycosat:

python3.13 -m pip install pycosat - If it gives you a

Microsoft Visual C++ 14.0 or greater is required.error, visit this link and downloadMSVC v143 - VS 2022 C++ x64/x86 build tools (Latest)andWindows 10/11 SDK(depending on your system)

Testing pycosat installation:

After unzipping the project code and changing to the project code directory, run:

python3.13 pycosat_test.py

This should output:

[1, -2, -3, -4, 5].

Please let us know if you have issues with this setup. This is critical to completing the project, and we don't want you to spend your time fighting with this installation process.

Question 1 (2 points): Logic Warm-up

This question will give you practice working with logic. The logic.Expr data type used in the

project to represent propositional logic sentences.

Fill in the functions sentence1(), sentence2(), and sentence3() in

the file logicPlan.py, which ask you to create specific logic.Expr instances.

For sentence1(), create one logic.Expr instance that represents that the

following three sentences are true. Do not do any logical simplification, just put them in in this form in

this order.

\[ A \lor B \]

\[ \neg A \Leftrightarrow \neg B \lor C \]

\[ \neg A \lor \neg B \lor C \]

For sentence2(), create one

logic.Expr instance that represents that the following four sentences are true. Again, do

not do any logical simplification, just put them in in this form in this order.

\[ C \Leftrightarrow B \lor D \]

\[ A \Rightarrow \neg B \land \neg D \]

\[ \neg (B \land \neg C) \Rightarrow A \]

\[ \neg D \Rightarrow C \]

For the planning problems later in the project, we will have

symbols with names like \(P[3, 4, 2]\) which represent that Pacman is at position \((3, 4)\) at time \(2\),

and we will use them in logic expressions like the above in place of \(A, B, C, D\). The

logic.PropSymbolExpr constructor is a useful tool for creating symbols like \(P[3, 4, 2]\) that

have numerical information encoded in their name (for this, you would type

PropSymbolExpr('P', 3, 4, 2)).

Using the logic.PropSymbolExpr constructor,

create symbols WumpusAlive[0], WumpusAlive[1], WumpusBorn[0],

and WumpusKilled[0], and create one logic.Expr instance which encodes the

following three English sentences as propositional logic in this order without any simplification:

The Wumpus is alive at time 1 if and only if he was alive at time 0 and he was not killed at time 0 or he was not alive at time 0 and he was born at time 0.

At time 0, the Wumpus cannot both be alive and be born.

The Wumpus is born at time 0.

Are sentence1(), sentence2(), and

sentence3() satisfiable? If so, try to find a satisfying assignment. (This is not graded, but

is a good self-check to make sure you understand what's happening here.)

Before you continue, try instantiating a small sentence, e.g.

\(A \land B \implies C\) and call logic.to_cnf on it. Inspect the output and make sure you

understand it (refer to AIMA section 7.5.2 for details on the algorithm logic.to_cnf

implements).

Now, implement a small function

findModel(sentence), which uses logic.to_cnf to convert the input sentence into

Conjunctive Normal Form (the form required by the SAT solver), then passes it to the SAT solver using

logic.pycoSAT to find a satisfying assignment to the symbols in sentence, i.e., a

model. A model is a dictionary of the symbols in your expression and a corresponding assignment of True or

False. You can test your code on sentence1(), sentence2(), and

sentence3() by opening an interactive session in Python and running

findModel(sentence1()) and similar queries for the other two. Do they match what you

thought?

To test and debug your code run:

python3.13 autograder.py -q q1

Question 2 (2 points): Logic Workout

Implement the following three logic expressions in logicPlan.py:

atLeastOne(literals): Return a single expression (Expr) in CNF that is true only if at least one expression in the input list is true. Each input expression will be a literal.atMostOne(literals): Return a single expression (Expr) in CNF that is true only if at most one expression in the input list is true. Each input expression will be a literal. There are multiple ways to implement this function. If you find your algorithm timing out on later problems maybe it is helpful to revisit the implementation of this function.exactlyOne(literals): Return a single expression (Expr) in CNF that is true only if exactly one expression in the input list is true. Each input expression will be a literal.

Each of these methods takes a list of logic.Expr literals and returns a single

logic.Expr expression that represents the appropriate logical relationship between the

expressions in the input list. An additional requirement is that the returned Expr must be in CNF

(conjunctive normal form). You may NOT use the logic.to_cnf function in your method

implementations (or any of the helper functions logic.eliminate_implications,

logic.move_not_inwards, and logic.distribute_and_over_or).

Important: When implementing your planning agents in the later questions, you will not have to

worry about CNF until right before sending your expression to the SAT solver (at which point you can use

findModelfrom question 1).logic.to_cnf implements the algorithm from section 7.5

in AIMA. However, on certain worst-case inputs, the direct implementation of this algorithm can result in an

exponentially sized sentences. In fact, a certain non-CNF implementation of one of these three functions is

one such worst case. So if you find yourself needing the functionality of atLeastOne,

atMostOne, or exactlyOne for a later question, make sure to use the functions

you've already implemented here to avoid accidentally coming up with that non-CNF alternative and passing it

to logic.to_cnf. If you do this, your code will be so slow that you can't even solve a 3x3 maze

with no walls.

You may utilize the logic.pl_true function to test the output of your expressions.

pl_true takes an expression and a model and returns True if and only if the expression is true

given the model.

To test and debug your code run:

python3.13 autograder.py -q q2

Question 3 (1 point): Extract the Solution

In future questions you will be assembling logic expressions to pass to a SAT solver. The SAT solver returns a model that will cause the logic expressions to be true. In the Pacman world, we need to convert this model into a specific sequence of actions ('North', 'South', 'East', 'West') that will lead Pacman to the goal.

Implement extractActionSequence(model, actions) in logicPlan.py, which returns an ordered

sequence of action strings based on the given model.

A model is a dictionary of the symbols in your expression and a corresponding assignment of True or False.

The keys in the model dictionary will be symbols in the form of a logic.PropSymbolExpr. The

model will contain assignments of True/False to many different symbols used in the Pacman world. Within the

many symbols in the model, some of them will be action symbols. Each action will have a different symbol for

each time point. For example 'East[3]', represents the symbol for taking the action 'East' at time t=3. This

method must find the actions symbols that are true in the model and return an ordered list of action

strings. The variable actions contain all of the possible actions that could be taken at any

time point. Each action symbol will follow the very specific format of action_string[t] where

action_string is one of actions and t will range from 0 to max_time - 1.

For your convenience, we've included the method logic.parseExpr which will do the regex

parsing of a symbol in one of these formats for you. Look at that function in logic.py to read

its output format.

To test and debug your code run:

python3.13 autograder.py -q q3

Example test code:

import logicPlan

from logic import PropSymbolExpr as PSE

model = {PSE("North",2):True, PSE("P",3,4,1):True, PSE("P",3,3,1):False, PSE("West",0):True, PSE("GhostScary"):True, PSE("West",2):False, PSE("South",1):True, PSE("East",0):False}

actions = ['North', 'South', 'East', 'West']

plan = logicPlan.extractActionSequence(model, actions)

print(plan)

The above should print: ['West', 'South', 'North']

Question 4 (2 points): Pacman Successor State Axioms

Implement pacmanSuccessorStateAxioms(x, y, t, walls_grid) in logicPlan.py.

This function takes in a position as x and y, a time t, and

walls_grid, which is a game.Grid object representing where the walls on the board

are (refer to the Grid class for documentation). The function should return the successor state

axiom for Pacman's position being (x,y) at time t.

We will use 'P' as the string for Pacman's location. That is, the symbol that "Pacman is at

position (3, 4) at time 2" should be P[3, 4, 2]. In your code, you should use the constant

pacman_str to represent this (so logic.PropSymbolExpr(pacman_str, 3, 4, 2) will

return P[3, 4, 2]).

Remember that the general formula for successor state axioms is

\[ X[t] \Leftrightarrow (X[t-1] \land \text{Nothing caused \(\neg X\) at time \(t-1\)}) \lor (\neg X[t-1] \land \text{Something caused \(X\) at time \(t-1\)}) \]

However, in this problem, the 'Stop' action is not allowed, so Pacman's position will always change. This gives instead the formula

\[ P[x, y, t] \Leftrightarrow \text{Pacman was at an adjacent square at \(t-1\)} \land \text{Pacman moved into \((x,y)\) at \(t-1\)} \]

Your job is to break this down into the possibilities for how Pacman could've moved into this square at this time.

Note: the possible adjacent squares Pacman could have previously been in depends on where the walls are.

To test and debug your code run:

python3.13 autograder.py -q q4

Hint: If you are struggling, try re-reading AIMA chapter 7.7, "Agents Based on Propositional Logic."

Question 5 (1 point): Generate All Transitions

Now that you have implemented the pacmanSuccessorStateAxioms(x, y, t, walls_grid) function

which gives us the successor state axiom for Pacman’s position being (x,y) at time

t, we can now build upon this to Pacman find the end of the maze (the goal position).

In order to help Pacman find this path through the use of propositional expressions, we must consider the

logical axioms that move Pacman from one location to another. At each time step, we need to include the

information that Pacman could be at any location on the board that is not a wall. Implement the

generateAllTransitions(t, walls) method to return a list of all Pacman successor state axioms

that are true at the given time.

You may find it useful to use the pacmanSuccessorStateAxioms(x, y, t, walls_grid) function you

wrote in the previous task.

To test and debug your code run:

python3.13 autograder.py -q q5

Question 6 (4 points): Solve the Maze

Pacman is trying to find the end of the maze (the goal position). Implement the following method using propositional logic to plan Pacman's sequence of actions leading him to the goal:

positionLogicPlan(problem): Given an instance oflogicPlan.PlanningProblem, returns a sequence of action strings for the Pacman agent to execute.

You will not be implementing a search algorithm, but creating expressions that represent the Pacman game logic at all possible positions at each time step. This means that at each time step, you should be adding rules for all possible locations on the grid, not just around Pacman's current location.

To build these expressions, think about what you know about the problem: where Pacman starts, the logical axioms that move him to the next state, the actions Pacman can take, and the goal state. Which can be formulated as logical expressions? Which of these have strict requirements on how many are true at each time step? Think about whether the axioms be applied to every state or only some states at every time step.

To find a model that satisfies your logical expression, you should call findModel from

question 1.

You should gradually increase the max time step until you find a model that satisfies all the expressions from time 0 to the max time step.

We will not test your code on any layouts that require more than 50 time steps.

Your function needs ultimately to return a list of actions that will lead the agent from the start to the goal. These actions all have to be legal moves (valid directions, no moving through walls).

Note: You will not be implementing a search algorithm, but creating expressions that represent the Pacman game logic at all possible positions at each time step. Do not search backwards from the goal.

Test your code on smaller mazes using:

python3.13 pacman.py -l maze2x2 -p LogicAgent -a fn=plp

python3.13 pacman.py -l tinyMaze -p LogicAgent -a fn=plp

To test and debug your code run:

python3.13 autograder.py -q q6

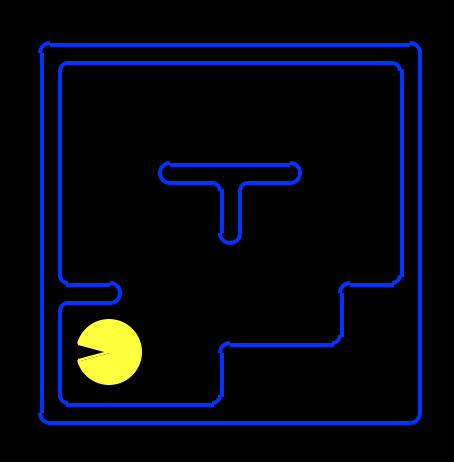

Note that with the way we have Pacman's grid laid out, the leftmost, bottommost space occupiable by Pacman (assuming there isn't a wall there) is (1, 1), as shown below (not (0, 0)).

Hint: You already implemented the successor state axioms which detail how Pacman moves. What's missing is where he starts, where his goal is, and that he must take an action every turn.

Hint: Remember to use atLeastOne, atMostOne, and exactlyOne

from question 2 if you ever need that functionality.

Hint: If you are struggling, try re-reading AIMA chapter 7.7, "Agents Based on Propositional Logic."

Debugging hints:

- If you're finding a length-0 or a length-1 solution: is it enough to simply have axioms for where Pacman is at a given time? What's to prevent him from also being in other places?

- Coming up with some of these plans can take a long time. It's useful to have a print statement in your main loop so you can monitor your progress while it's computing.

- If your solution is taking more than a couple minutes to finish running, you may want to revisit

implementation of

exactlyOneandatMostOne(if you rely on those), and ensure that you're using as few clauses as possible.

Question 7 (4 points): Eat the Food

Pacman is trying to eat all of the food on the board. This is the same problem setup as the search problems in Project 1. Implement the following method using propositional logic to plan Pacman's sequence of actions leading him to the goal.

foodLogicPlan(problem): Given an instance oflogicPlan.PlanningProblem, returns a sequence of action strings for the Pacman agent to execute.

This question has the same general format as question 6. The notes and hints from question 6 apply to this question as well. You are responsible for implementing whichever successor state axioms are necessary that were not implemented in previous questions.

Test your code using:

python3.13 pacman.py -l testSearch -p LogicAgent -a fn=flp,prob=FoodPlanningProblem

We will not test your code on any layouts that require more than 50 time steps.

To test and debug your code run:

python3.13 autograder.py -q q7

Hints:

- How does the goal change from the maze navigation task to the food consumption task?

- How can you encode your new goal as a conjunction of sub-goals that must be accomplished? What must be true/have occurred for each of these sub-goals to be accomplished?

- Remember that propositional logic works in terms of binary True/False, not integers- don’t try to engineer an integer food counter.

GraphPlan Setup

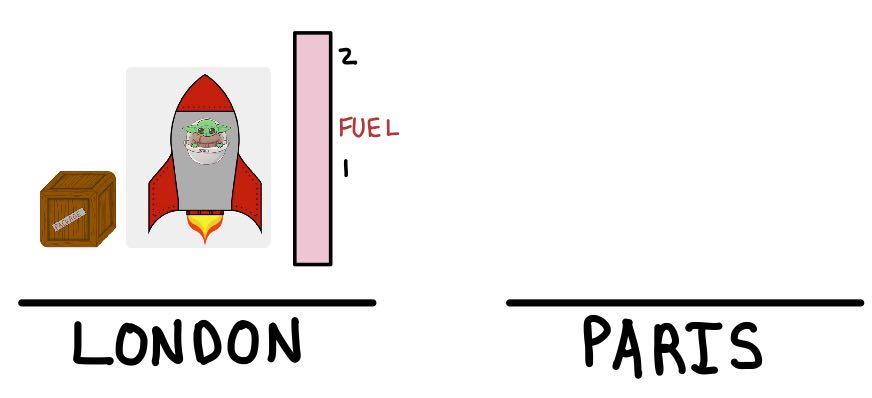

You have implemented a framework for Pacman to find its way to the goal using logic-based planning. Now you will implement a framework for Pacman to find the same goals using the classical planning algorithm GraphPlan. Similar to LogicPlan, you will represent Pacman at locations in his maze. Each part of Pacman's state must be implemented as booleans, similar to LogicPlan. However, unlike LogicPlan, you will not explicitly represent time and you will not make unique symbols for each possible Pacman state. Instead, the GraphPlan solver uses your implementation of actions (operators) which explicitly add and delete propositions in the state to enumerate the possible state propositions at each level of the planning graph and those levels represent time. While LogicPlan searches for a satisfying set of variables to plan a path, GraphPlan will search for the first level when all goal propositions are present and not mutually exclusive (i.e., all goals can be met at the same time).

Our GraphPlan solver represents the world using Instances, Variables, Propositions, and Operators.

For an example of a GraphPlanProblem formulation, look at rocket.py. You can run this using:

python3.13 rocket.py

Instances are all of the literals and constants in the model. Each Instance has a Type. In the rocket example, London and Paris are Instances of Type PLACE; the rocket is an Instance of Type ROCKET; the package is of type CARGO.

# Types

ROCKET = 'Rocket'

PLACE = 'Place'

CARGO = 'Cargo'

# Instances

i_rocket = Instance('rocket', ROCKET)

i_london = Instance('london', PLACE)

i_paris = Instance('paris', PLACE)

i_package = Instance('package', CARGO)

(You do not have to follow the i_ naming convention, but we have done so here for clarity.)

Because the planner deals only in Instances, any integers you want to use must be declared as INT types. The rocket example includes those as well. You will be responsible for creating any Instances (including ints!) you use in your implementation.

For the rocket problem, we need these INT instances to represent how much fuel the rocket has remaining (as we know it can only be an integer value between 0 and 2).

Important: Why is it important to know that integers are instances? 1) Because we can't add and subtract them as normal integers. We'll have to utilize propositions to relate integer instances to each other (adding or subtracting 1, for instance). and 2) Because it means we can create new propositions that also use integers (e.g., fuel for a rocket or grid square indices that are open or walls).

Important: We will need to reference the instances later in the problem. We can set Python variables equal to the Instances as seen above. We can also make lists of instances:

i_ints = [Instance(0, INT), Instance(1, INT), Instance(2, INT)]

#i_ints[0] references the instance of the integer 0

Variables can take the value of any Instance of the same Type. For example, in the rocket problem we created a variable. Note that the variables are more like placeholders. You don't directly assign values to them, but instead use them to specify the effects of the operators. The variables will bind to the actual instances when an operator is selected.

v_from = Variable('from', PLACE)

which can take the value of any possible place that we have created. Note that the string 'from' must be unique in the environment. You will use these variables in your operators.

Propositions are boolean descriptors of the environment and act like functions that return a

boolean. We write Proposition('boolean_desc', instance/variable1, instance/variable2) if

instance1/variable1 and instance2/variable2 are related by boolean_desc, and we write

~Proposition('boolean_desc', instance1/variable1, instance2/variable2) if the relationship is

false. For example, if the rocket is starting at the instance for London then it is 'at' London and

not 'at' Paris.

Proposition('at', i_rocket, i_london)

~Proposition('at', i_rocket, i_paris)

In our implementation, the first argument is a string descriptor of your choice, which you can think of

as just a name that identifies the proposition. The other arguments (instances or variables) are like the

inputs for the proposition. Propositions can take in as many arguments as we want but must remain constant

when we use them. For example, a proposition for the rocket being 'at' the location i_london

can be written as Proposition('at', i_rocket, i_london), and later should not be called as

Proposition('at', i_london). At any given state, i.e., the initial state, we can define that

state as a set of propositions, or things that are true or false at that given point in time. The list

[Proposition('at', i_rocket, i_london), ~Proposition('at', i_rocket, i_paris)] represents the

conjunction of those propositions. To move from state to state, we will be adding and removing

propositions from this list.

One special proposition that GraphPlan provides, SUM, checks whether two integer instances sum to the third.

i1 = Instance(1, INT)

i2 = Instance(2, INT)

Proposition(SUM, i1, i1, i2)

SUM is defined for you in graphplanUtils.py and does not need to be added explicitly to the

initial state but can still be used in operators. The rocket example uses SUM to compute the amount of

fuel left.

To define the start and goal states of the problem at hand, we use lists of Propositions. For instance, the starting state of the Rocket problem is that the package and rocket are at London, and the rocket’s fuel level is 2.

We represent this state as follows:

[Proposition('at', i_package, i_london),

Proposition('at', i_rocket, i_london),

Proposition('fuel_at', i_ints[2])]

The goal is for the package to be in Paris, and the rocket to be in London. Note that we do not specify the state of the rocket’s fuel level, so the fuel level can be anything.

We represent these goals as follows:

[Proposition('at', i_package, i_paris), Proposition('at', i_rocket, i_london)]

Operators contain lists of preconditions, add effects, and delete effects which are all composed of propositions. Operators will test the current state propositions to determine whether all the preconditions are true by matching available instances and/or variables, and if so then add and delete state propositions to update the state.

i_rocket = Instance('rocket', ROCKET)

i_london = Instance('london', PLACE)

v_fuel_start = Variable('start fuel', INT)

v_fuel_end = Variable('end fuel', INT)

v_from = Variable('from', PLACE)

v_to = Variable('to', PLACE)

o_move = Operator('move', # The name of the action

# Preconditions

[Proposition(NOT_EQUAL, v_from, v_to),

Proposition('at', i_rocket, v_from),

Proposition('fuel_at', v_fuel_start),

Proposition(LESS_THAN, i_ints[0], v_fuel_start),

Proposition(SUM, i_ints[1], v_fuel_end, v_fuel_start)],

# Add effects

[Proposition('at', i_rocket, v_to),

Proposition('fuel_at', v_fuel_end)],

# Delete effects

[Proposition('at', i_rocket, v_from),

Proposition('fuel_at', v_fuel_start)])

We read the operator in the following way. In order to perform the move operation, the

source (v_from) must not equal the destination (v_to); the rocket must be at the

source; the rocket must have v_fuel_start units of fuel such that

v_fuel_start > 0 and v_fuel_end + 1 = v_fuel_start. The GraphPlan implementation

will find ALL satisfying assignments of instances to the variables such that these preconditions are true.

For each one, it will perform the adds (making each of these propositions true is a way of saying that the

rocket is now at the instance assigned to variable v_to and the fuel is now at the instance assigned to

v_fuel_end) and deletes. Note that a delete does not make the negation of the defined propositions true.

All possible ways to match the move operator would each be represented in the action layer of the

GraphPlan graph.

Note: If the proposition must match the state exactly in the precondition or effects, use an instance. If any instance can be matched, use a variable of the correct type.

For example, one precondition of the "move" Operator is that the rocket’s destination is different from

its current location. We can specify this by the Propositions

Proposition('at', i_rocket, v_from) and Proposition(NOT_EQUAL, v_from, v_to).

Here, we only care about the one rocket Instance’s movement, so we used the i_rocket

Instance. As for the PLACE variables, any Variables that satisfy the NOT_EQUAL requirement could be

matched (i.e., we could have v_from matched with the London Instance and v_to

matched with Paris, or vice versa. Note that whatever v_from is matched to is used throughout

the entire Operator. That same Instance must also satisfy the

Proposition('at', i_rocket, v_from) precondition, and will be used in the delete effect as

well.

After moving, the rocket is now at the destination and has v_fuel_end units of fuel. It is

no longer at the source and no longer has v_fuel_start units of fuel. The following image

depicts an example of a state that would satisfy the preconditions and be able to move.

This state, however, does not satisfy the preconditions for move, as the starting fuel is not greater than 0.

Note that the variables must be defined before an operator can use them and that you should not replicate integer instances. Also note that ~Proposition and Proposition are not mutually exclusive in our implementation. You must explicitly delete propositions in your operators or explicitly add their negations. The absence of a Proposition means it may or may not be true. For example, if we wanted to say that the rocket is not in Paris, we would need ~Proposition(‘at’, i_rocket, i_paris) to be true.

Key takeaway: While searching for a plan, GraphPlan tries to match the Variables mentioned in the Operators with Instances (in a way such that the preconditions of the Operator are satisfied).

Question 8 (1 point): Analyzing the Rocket Problem

Before diving into the implementation of GraphPlan for Pacman, we want you to perform some analysis on

the already implemented rocket problem described above in order to help better increase your understanding

of how GraphPlan works. It will also help in understanding the interaction is between the Instances,

Propositions and Variables. We may ask you to make modifications to rocket.py and report on

the results. To view the full output with what happens at each level of GraphPlan, uncomment the last line

of the file and rerun. This may prove useful in understanding how the algorithm finds the solution as well

as why it doesn’t find a solution in other cases.

- At what level of the planning graph was the solution found? If no solution is found, return

"NO SOLUTION". - How many proposition nodes and action nodes do we have at level 1 of the planning graph? Give your

answer as a tuple

(# proposition nodes, # action nodes). - If we change the starting state to start at a fuel level of 1 instead of 2, why do we not find a

solution?

A) Mutually exclusive goals, B) goals missing, or C) None of the above, a solution is found.

In the file analysis.py you will return your answers to each of the above questions in their

corresponding functions. You must get all three questions correct in order to get the point for the task.

We will not tell you which answer is incorrect or how many.

To test and debug your code run:

python3.13 autograder.py -q q8 Question 9 (4 points): Solve the Maze Using GraphPlan

Pacman is trying to find the end of the maze, again. This is the same as Q5 except you are asked to use graph planning instead of propositional logic. Implement the following method by modelling the problem as a graph planning problem to plan Pacman's sequence of actions leading him to the goal:

positionGraphPlan(problem): Given an instance ofgraphPlan.PlanningProblem, returns a sequence of action strings for the Pacman agent to execute.

You should think about the axioms defined in Q4, and define operators

[o_west, o_east, o_north, o_south] (and necessary variables) that allow those axioms to be

achieved.

We have provided you with 3 types - PACMAN, FOOD, and OPEN (which represents the absence of a wall) - in

addition to INT which is defined in graphPlanUtils.py. It is up to you to decide which are

necessary for the problems.

If you'd like to test your code before implementing all 4 operators, you can run

python3.13 pacman.py -p GraphPlanAgent -a fn=positionGraphPlan,prob=PositionPlanningProblem -l <LAYOUT>

With <LAYOUT> being one of:

mazeDown: only requireso_southto solve.mazeLshape: only requireso_southando_westto solve.mazeUshape: only requireso_south,o_west, ando_northto solve.

Test your code with all 4 operators using:

python3.13 pacman.py -p GraphPlanAgent -a fn=positionGraphPlan,prob=PositionPlanningProblem -l tinyMaze

And for a challenge, try

python3.13 pacman.py -p GraphPlanAgent -a fn=positionGraphPlan,prob=PositionPlanningProblem -l smallModifiedMaze

Note: Your function needs to return a list of actions ('North', 'South', 'East',

'West') that Pacman can use to go from the start to the goal. These actions all have to be legal moves

(valid directions, no moving through walls). We have provided you with example code of generating and

solving a GraphPlan problem in rocket.py.

Hint:

You need to represent the open squares where Pacman can move into, but you can’t use tuples (x,y). There are several ways to do this; here are a few to consider.

One way is to create an instance i_x for each x and i_y for each

y value (numbers must be instances) and then create Open propositions where

Open(i_x,i_y) if the location x,y is open. How would you represent Pacman’s location if

open squares are presented this way? How would you represent moving North, South, East, or West? In this

representation, you need to reason about the numbers i_x and i_y, so your

answers to these questions should be in terms of those values.

Another way to represent open squares is to create an instance i_open_xy for each open

square and an AtX(i_open_xy, i_x) and AtY(i_open_xy, i_y) proposition

representing that the instance is at the x and y locations. Then, you have an

instance i_open_xy for pacman to be located at, but how do you represent the transitions

North, South, East, and West to check if they are valid? And how would you know if the new location was

valid?

You certainly don't have to solve the problem these ways, but hopefully these ideas get you started at thinking about how to represent the problem.

Important: You will have to translate the GraphPlan actions into Pacman actions to

return. To get the string names of a GraphPlan ActionNodes in the returned solution, you can use

action.print_name().

To test and debug your code run:

python3.13 autograder.py -q q9

Question 10 (4 points): Eat the Food Using GraphPlan

Pacman is trying to eat all of the food on the board, again. This is the same as Q7 except you are asked to use graph planning instead of propositional logic. Implement the following method by modelling the problem as a graph planning problem to plan Pacman's sequence of actions leading him to the goal.

foodGraphPlan(problem): Given an instance ofgraphPlan.PlanningProblem, returns a sequence of action strings for the Pacman agent to execute.

Test your code on a smaller layout using:

python3.13 pacman.py -p GraphPlanAgent -a fn=foodGraphPlan,prob=FoodPlanningProblem -l tinyMaze

If you want to test your code on increasingly more complex layouts, run

python3.13 pacman.py -p GraphPlanAgent -a fn=foodGraphPlan,prob=FoodPlanningProblem -l <LAYOUT>

With <LAYOUT> being one of mazeSearch1 or mazeSearch2.

You should be using move actions as in Q9 and adding an operator o_eat to eat the food.

Think about when food can be eaten and look at the start state and goal state to determine which

propositions you should modify. However, make sure that the action list returned does not include the eat

action (eating food is implied in that model).

To test and debug your code run:

python3.13 autograder.py -q q10

Submission

Complete Questions 1 through 10 as specified in the project instructions. Then upload

logicPlan.py, analysis.py, and graphPlan.py to Gradescope.

Prior to submitting, be sure you run the autograder on your own machine. Running the autograder locally will help you to debug and expediate your development process. The autograder can be invoked on your own machine using the command:

python3.13 autograder.py

To run the autograder on a single question, such as question 3, invoke it by

python3.13 autograder.py -q q3

Note that running the autograder locally will not register your grades with us. Remember to submit your code when you want to register your grades for this assignment.

The autograder on Gradescope might take a while but don't worry: so long as you submit before the due date, it's not late.